New article from Alexander Fetisov, this time about agricultural tools. References to the in-depth study are attached.

Arable implements of the 9th - 11th centuries - the topic most connected in archeology with ethnographic parallels. In archaeological material from such tools (with rare exceptions) only metal elements are preserved - attachments for working parts. The very design of the tools, their functional and target features cannot be reconstructed using these tips alone. Therefore, the main material for reconstructions here is provided by ethnographic material of the 18th - 20th centuries. and quite numerous medieval miniatures depicting agricultural work.

In specific rural communities, culture and agriculture have developed in parallel, adapting to constant change environment... This is evidenced by the knowledge that he has about the components of the agroecosystem present in his environment, such as: the rainy season and sowing, droughts, hail, winds, pests and diseases, type of land, fertilizers and fertilizers. tools and others.

In the context of the complexity of peasant agriculture, its actors have a wide repertoire of knowledge. Emphasizes the traditional approach focused on the management of production systems, the purpose of which is to ensure their physical and social reproduction. Part of the importance is also reflected in its ability to minimize risks with efficient production derived from a mixture of crops, restoring soil fertility by rotating with legumes. This is also reflected in the quality and usefulness of interpreting natural phenomena such as lunar cycles, climate and life cycles species.

In the earliest written sources of all arable implements are mentioned "ralo" and "plow", from the XIII century. - "plow". What is noteworthy is that the word "plow" in the meaning of an arable tool is exclusively East Slavic, the South and West Slavs do not have this term in this meaning.

A generally accepted classification of arable implements has not yet been developed. Therefore, following A.V. Chernetsov and Yu.A. Krasnov take the following general typology:

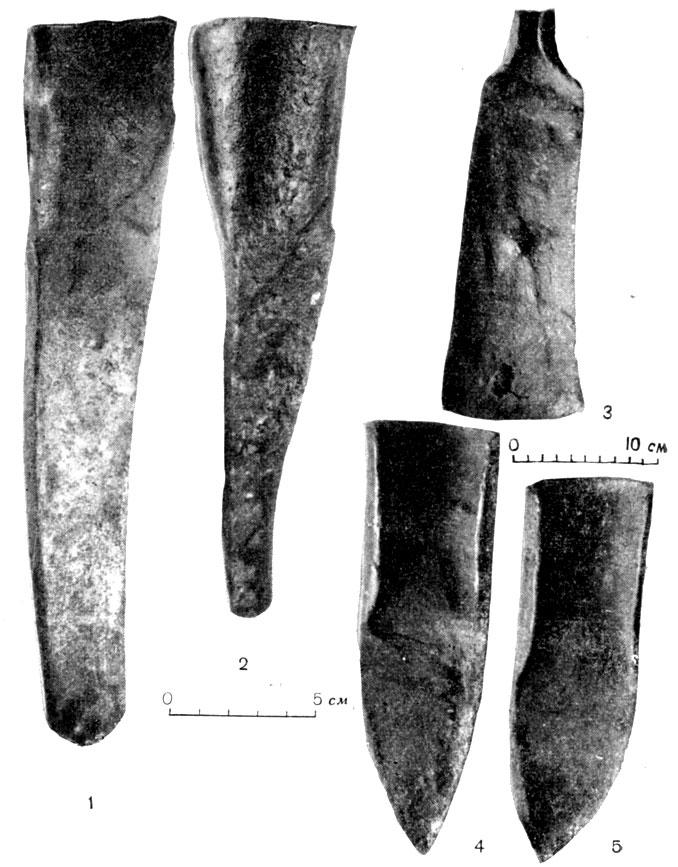

Ralo is a tool for symmetrical plowing without turning the soil layer. Archaeologically, the rao is fixed according to the characteristic attachments on the working part - natralniks - broad-bladed tips with shoulders.

Another aspect is soil knowledge, since the existence of knowledge and its classification by the groups of Nahua, Maya, Tarascana, Otomi and Zapoteka has been demonstrated since pre-Hispanic times. In fact, this knowledge is believed to be present throughout Mexican society, which originates from ancient Mexico. In this sense, in his work on the classification of Nahuatl soils, Williams points out that 45 classes were known for administrative use and management purposes, each represented in codices by means of glyphs.

For peasant research, it is customary to generalize traditional knowledge without taking into account environmental variables or factors such as erosion of agricultural land, energy waste of working animals or machinery, investment of time and labor of peasants and those involved in the process or making decisions about the choice of seed to be cultivated. among others. However, in many cases, formal research also does not account for sociocultural variables. Therefore, despite the presence of other variables, this study focuses on highlighting the importance and value of traditional knowledge in agricultural practices for crop management, production forms and the use of tools associated with the amaranth growing system from the municipality of Tochimilco, Puebla.

The plow is a two-toothed tool with a high center of gravity. One draft animal was used for the plow. The main difference between the plow and the ral since the time of D.K. Zelenina is considered to be two-toed. The Ralo had one metal tip, the plow had two. Archaeologically, it is fixed by metal nozzles on the working part - openers - narrower and longer than the openers.

The plow makes a full or partial rotation of the soil layer and produces asymmetrical one-sided plowing. One or more pairs of draft animals were usually used for the plow. The main difference between the plow and the rally is the presence of a one-sided blade. Archaeologically, it can also be recorded for several elements. The metal tip of the plow (the share is larger and heavier than the share) was supplemented in the design with a special iron plow knife (pechal), which was installed in front of the share.

According to the level of development, these arable implements can be arranged in the following sequence: ralo - plow - plow. But at the same time, it does not mean at all that these tools chronologically replaced each other - they were used simultaneously, depending on the types of farming systems and regions.

The study was conducted in the municipality of Tochimilco, which is located in western Puebla. Tochimilko's economic activity is predominantly agricultural, with maize, beans and amaranth as the main crops. This area was chosen due to the fact that the latter is important for the inhabitants of the municipality and for being the first producer at the national level in the production of seeds.

The population of amaranth farmers was studied in the municipality of Tochimilco, Puebla. The sample size was obtained using the formula. The collection of information was carried out using observational and field travel techniques and was complemented by semi-structured interviews conducted by 83 producers, which provided guidance on issues that covered topics such as producer socioeconomic characteristics, land tenure, producer-farmer relationships and interactions and actors associated with the agricultural system, as well as the tools and technologies used in the system, cultivation activities carried out throughout the cycle, management from land preparation to harvest, soil and climate knowledge associated with crop management, costs production, the way they sell the grain, the value that the cultivation of amaranth represents for them, and how the culture has improved their living conditions.

Ralo.

Structurally, the early Middle Ages were a fairly simple weapon. It consists of two main parts. Actually the rao (as a rule, curved), one end of which ended with a handle, and on the other end a metal head was placed; and a bar (bend) attached to the ral, with the help of which traction animals were harnessed.

These interviews were distributed in major settlementswhere amaranth is grown in the municipality: 25 in the municipal area, 30 in Tohimizolco, 15 in San Miguel Tequanipan and 13 in San Lucas Tulzeo. Data analysis was carried out using a hermeneutic method, which, according to Taberner, consists in the interpretation of discourse data, such as a census or empirical record or opinions in a given context. It is a method of interpretation that tries to understand texts and discourses; it consists in going beyond the superficial meaning to reach a deep meaning, even hidden; find multiple feelings when there seems to be only one; especially to find an authentic meaning related to the intention of one element of the hermeneutic circle: the author, the text and the reader.

According to the arrangement of the working part, the rallies are divided into two types - useless, in which the head is at a significant angle to the ground; and skid, in which the working part is close to the horizontal position relative to the ground. Useless Rala cultivated the land only with the end of the shaft, plowed shallow, did not completely destroy the roots of weeds. But at the same time useless rallies were very "maneuverable" and when working with them it was easy to change the plowing depth. This was very convenient when working on shallow soils, where deep plowing is harmful. Rala with a runner could be used on soils with a deep arable layer, homogeneous and "not littered" by stones, roots and stumps.

The zone producer aims to improve the management of amaranth cultivation by using traditional knowledge and tools augmented by technology to increase the income of the production unit in order to support its reproduction. In his agriculture small-scale and seasonal, human and animal hunting prevails over mechanized work, with full dependence on precipitation, which indicates that there is a deep physical and biotic knowledge of the environment, which is "reorganized", in accordance with the needs, interests and economic opportunities and base farmers' knowledge to deal with problems identified in the agricultural system, “acceptance” when they find that knowledge from institutions, agents or producers themselves is relevant to cultivation and “adaptation” when it is not fully aligned with the farmer's capabilities and land needs.

Archaeological sites VIII – X centuries. - these are rather wide (broad-bladed) tips with an open sleeve elongated in cross section. The length of the forefoot is from 16 to 22 cm, the width of the blade is 8 - 12 cm, the width of the sleeve is 6 - 8 cm. The main zone of distribution of the forefoot is the border of the forest-steppe and steppe bands and the steppe band. However, they are also found in Northern Russia (Novgorod, Ladoga, Beloozero), where from the 9th century. were used simultaneously with the plow.

According to information collected from interviews applied to 83 amaranth growers, the average age of producers was 55 years. The average area on which they grow amaranth was 4 hectares in different areas, on 100% seasonal land. Traditional knowledge in agricultural practice related to the environment.

When you ask farmers why, how and when is the most appropriate time to do the work of growing in amaranth, the first thing they answered was that it depends on the time, which usually has two estimates in accordance with the worldview of the producer, the understanding by the worldview of that how peasants perceive and interpret nature through their beliefs, knowledge and practices. The first refers to nature, which stems from the interpretation of space and includes planting dates and weather based on natural observations such as wind direction, humidity, cold and sun, among others.

The second relates to the religion in which natural phenomenaassociated with the oncomatter of the "saints" revered in the area and in the community, as well as special days of the year that provide information such as the wild boars of the beginning of the year and interpret the lunar phases for cultural harvest work.

These actions correspond to the close relationship between man and nature, the product of traditional knowledge inherited from parents to children. The traditional knowledge of the environment held by the farmer is vital in making decisions about establishing the harvest. This is assumed because 100% of the respondents answered; Based on the knowledge inherited by their predecessors and their own experience, the best time to plant is the first 15 days of June, as this is the date when the rains start with more uniformity.

Sokha.

Sokha is extremely interesting and, one might even say, original russian gun... Etymologically, for example, in the languages \u200b\u200bof the non-Slavic environment (Finns, Balts, late medieval peoples of the Volga region), the word for plow goes back to the East Slavic - which means that this tool came to them from the Slavic world. Having originated among the Eastern Slavs in the second half - the end of the VIII century, the plow already in the XII - XIV centuries. widely spread throughout Eastern and Central Europe, becoming universal in the late Middle Ages arable tool for almost any purpose and any type of farming.

However, according to producers, due to climate change, despite the establishment of sowing dates, they are changed or adjusted. In addition, they express that they take into account the lunar phases in the management of cultures. For example, think that the best time to plant is when the moon is in the first quarter because there will be more fruit. Harvesting, threshing and harvesting takes place at the end of the weakening phase to ensure that the grain is in the best storage conditions.

Traditional knowledge of soil. According to their experience and inherited knowledge, farmers distinguish between the types, quality and physical characteristics of soil and its behavior when interacting with moisture. Soil types differ in color, texture and position, in addition to the ones they add to organic matter, and identify them by their ability to retain moisture.

The main working part of the plow - rassokha - is curved in the longitudinal plane and bifurcated at the end of a wide block or board, to which two metal openers were attached from below. The height of the rassokh was determined by the height of the plowman and, according to ethnographic materials, as a rule, did not exceed a meter. As an exception, single-toothed and multi-toothed (three to five teeth) plows are known, but only based on ethnographic materials of the 19th century. The top end of the rass was attached to a horizontal bar (bagel), the ends of which served as handles. And since the shafts for harnessing the cattle were attached to the same bagel, the plow received a high (in contrast to the wheel and plow), at the level of the plowman's hands, the application of traction force. In fact, when plowing with the plow, the traction animal was less loaded than when plowing. Therefore, one animal was harnessed to the plow (horse or c.s.), and a couple or several pairs were harnessed to the plow.

They classify the soils that exist on their farms and, depending on this, set the amaranth yield and provide specific control in soils with heavy or open textures, as well as in sandy soils. They state that Tochimilco is dominated by sandy and well-drained soils, which coincides with Tello Garcia's expression, citing that amaranth can be grown in soils with varying nutrient levels, although its best development occurs in sandy, well-drained and with a good nitrogen balance. and phosphorus.

Agricultural methods used to grow amaranth. Today, the introduction of the concept of sustainability refers to the multitude of processes that make up it, since it is nothing more than a term; it new image thinking and acting for which people, culture and nature are inseparable from each other, as they seek the well-being of people without compromising the balance of the environment and its natural resources for both the current generation and future generations. However, to the extent that more research is being done in the agricultural sector, many of the peasant customs that were previously considered rudimentary are being revised and recognized as appropriate for conserving natural resources.

The main differences between the plow and plows and ral were the manufacture of all its parts from separate parts; the presence of a horn (there is no such element in plows and rallies); bifurcated working part; high place of application of traction force; the use of bast, rope or twigs (rootstocks) to adjust the angle of installation of the rake relative to the shafts (that is, the angle of the working tips relative to the ground level). The rootstocks functionally matched the wooden racks and plows, and survived unchanged until the 19th century, when this soft connection began to be replaced by a wooden rod or an iron rod with screws.

According to ethnographic materials, plows are quite complex in design with additional elements that made it possible to turn the soil layer to the side (reversible plows, one-sided plows, roe plows) - that is, the tools are already close to the plow. However, nothing is known about the existence of such types in the early Middle Ages - most likely, they appeared around the 16th – 18th centuries.

Almost all finds of openers are concentrated in the forest area of Eastern Europe... The tips of plows, ral and plow knives are spread further south. It is believed that initially, in the VIII-X centuries. the plow was intended for work in the conditions of forest fallow and the transformation of undercutting into long-term fields - therefore, the plow could be used simultaneously with the plows that successfully worked on old arable lands and on relatively clean lands that had long been freed from forests.

Farmers in the study area have developed production systems based on their agricultural practices and management, such as preparing the land, selecting seeds for planting, feeding the crop with poultry manure, pest control, and creating their own tools. among others In this row, the use of tools and mechanisms in agricultural practice that are carried out in the harvest of amaranth in the study area is shown in Table 2.

Land preparation: Farmers stated that they are doing paired work to ensure that the land “regenerates” and contains sufficient moisture from the rain for the next cycle. This activity is complemented by harrowing, mainly to prevent the evaporation of trapped moisture and eliminate weeds. Traditionally, a ferry with a wooden plow and a steel tip with animal traction and tracking is done by driving through a branch or a board pulled by horses after steam. It is important to emphasize that more than 30% of amaranth producers in this area have their own plows, and in situations of economic scarcity they carry out this activity with their own working group; however, under favorable economic conditions, the activities described above are carried out with the aid of a tractor in order to expedite this practice.

Long (18-20 cm) and narrow (6-8 cm) tips prevail among the openers. Opener sleeve width VIII - X centuries was 5 - 7 cm. Average weight - about 650 gr. The oldest tips of openers were found in Staraya Ladoga (second half of the 8th - first quarter of the 9th centuries) and at the settlement of Kholopiy Gorodok near Novgorod (late 8th - early 10th centuries). By the X century. a rare find of a wooden two-toothed rassokh in Staraya Ladoga belongs. In the X century. finds of openers are known in Timerevo, Vladimirskie kurgans (Bolshaya Brembola), Gnezdovo. In the XI - XII centuries. finds of openers are already widely known almost throughout the forest-steppe Rus, they appear both in the Baltic States and in the Finno-Ugric territories. The coulters were usually made from a solid piece of iron or mild steel.

A pair of openers.XIVin.

Plow.

In Central Europe, the plow, as a tool, the obligatory function of which is to turn over a layer of earth, appears in the first half of the 1st millennium AD. Based on the mention of the plow in the PVL when describing Vladimir's campaign against the Vyatichi in 981, it is believed that in the X century. the plow was already well known in the East Slavic world. However, not all so simple.

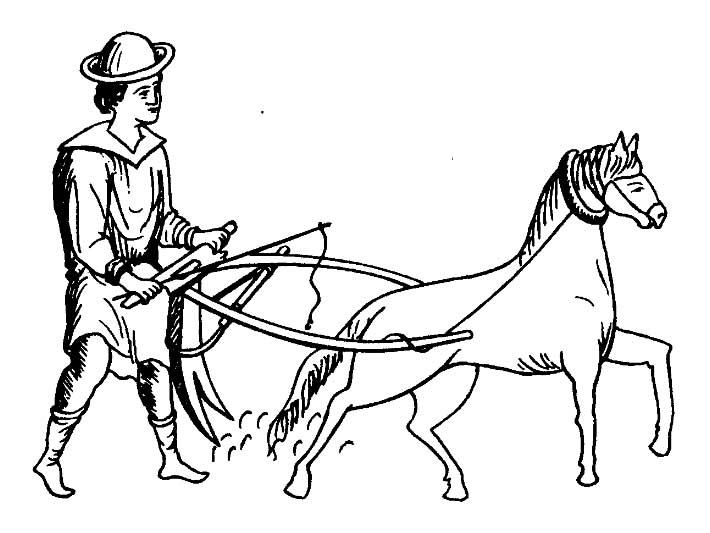

Plowing. Drawing of the painting of the Voronetsky monastery. Moldova. XVI century

The main parts of the plow, known from ethnography and from medieval miniatures, are the working part (runner), at the end of which a ploughshare is planted; plow knife (beetle); a dump that ensures the overturn of the earth layer to the side. Sometimes the plow could have a wheeled front end. The runner was usually double - it was made of two "bars", the ends of which were bent at the top, passing into the handle, and below they were connected under the plowshare nozzle. The essence of plowing with a plow: a layer of earth is cut with a vertically installed crescent, cut horizontally with a share, lifted with it and turned over to the side with a one-sided blade.

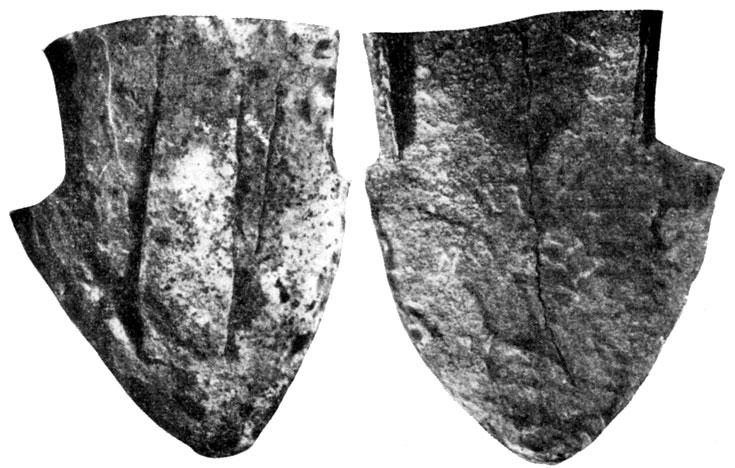

Archaeologically, however, it can be quite difficult to determine any details exactly as elements of a plow. The fact is that the main distinctive function of the plow - the revolution of the earth - was carried out by an element (blade), which for a long time in the Middle Ages it was made of wood, and therefore did not survive. The plow share differs from the headstock actually only in size - the plow has always been much larger than the rallying, which explains its high performance, design complexity and high cost. The length of pre-Mongol plowshares ranged from 18 to 26 cm, width - 12 - 19 cm, weight - from 1 to 3 kg. Plowshares of late medieval plows have an asymmetric shape, but in pre-Mongol Rus this feature was not yet fully formed - asymmetry at this time is recorded among plowshares quite rarely (Raikovetskoye settlement, Izyaslavl).

Asymmetric share.XII in.

Those tips, which are interpreted as symmetrical plow plowshares (based on their large size), of pre-Mongol Rus, as a rule, are quite widely dated to the end of the 10th - beginning of the 13th centuries. Pre-Mongol plowshares were made of two halves and sometimes even reinforced by welding additional strips. Plow tips with traces of repair are known.

Plow points dated more narrowly to the 9th - 10th centuries. not yet known. Therefore, it is probably too early to talk about the widespread distribution of the plow in Ancient Rus before the 11th century. It is possible that plowshares (if, of course, these are not natralniks) were found at the settlements of Khotomel (IX century) and Ekimautsky (X – first half of the XI centuries). Plow knives were also found there in both cases. .

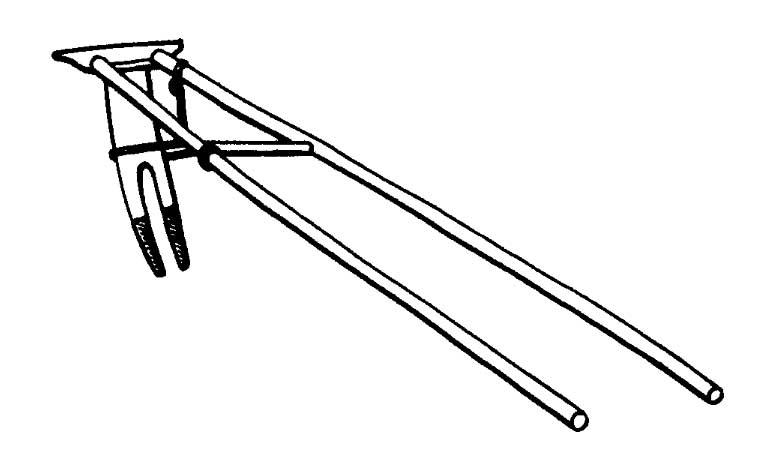

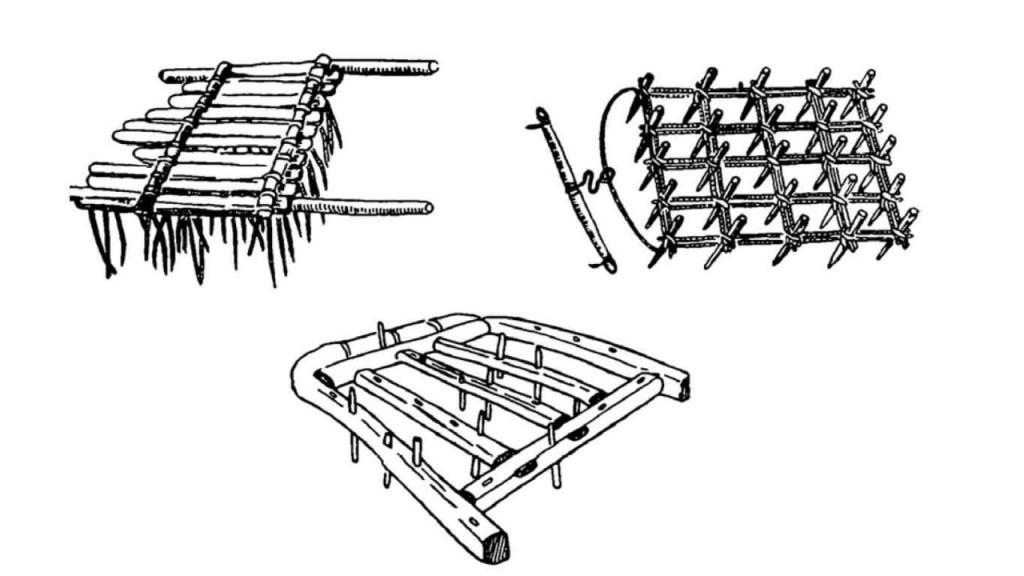

Harrow.

A harrow was used for post-tillage. The term "harrow" itself is found in the extended edition of "Russkaya Pravda" (early XII century) together with a plow.

Ethnographic types of Ukrainian harrows

The most ancient form is considered to be a knotted harrow made of spruce logs with knots.

Graphical reconstruction of a knotted harrow

In the archaeological material of the early Middle Ages, harrow parts are very rare, but still there. Wooden tooth of harrow X c was found in Staraya Ladoga .

Harrow tooth from Staraya Ladoga

Literature.

Dovzhenok V.I. Farming Drevnyoi Rusi. Kiev. 1961.

Krasnov Yu.A. Ancient and medieval agricultural implements of Eastern Europe. M. 1987.

Kolchin B.A. Ferrous metallurgy and metalworking in Ancient Russia (pre-Mongol period). M. 1953.

Chernetsov A.V. On the periodization of the early history of East Slavic arable tools // SA. 1972. No. 3.

Chernetsov A.V. On the study of the genesis of East Slavic arable tools // SE. 1975. No. 3.

The Russian people have long been an agricultural people. In the Laurentian Chronicle, which tells about the events of the initial period of Russian history, under the year 946 it says: "All your grad ... make their own fields and their own land." Agriculture remained the main branch of the Russian economy until the beginning of the 20th century. Along with growing grain, the Russian people were engaged in the cultivation of industrial crops (flax and hemp), horticulture and gardening.

The bulk of Russia's agricultural products were produced on peasant farms. This word was usually used to refer to a farm based on manual labor and draft power of animals, in which work was performed by a separate family without the use of hired labor. Each peasant farm had a certain amount of land, as well as a certain set of tools and vehicledesigned to work on it: tools for plowing, for sowing, for harvesting, for threshing and wind. In addition, the peasants used special mechanisms and devices for processing grain into flour, flax and hemp seeds into oil, their stems into fiber, and then into threads and fabrics.

All traditional implements peasant labor, with the exception of tillage, were the same throughout the territory of the settlement of the Russian people. For sowing grain, flax and hemp seeds throughout Russia, seeding baskets were used, for harvesting - sickles, for threshing grain crops - flails, for threshing flax and hemp - rolls, for winding - shovels, for processing grain into flour at home - millstones, a large amount of grain was processed in mills. For the processing of flax and hemp stalks into fiber, and fibers into thread and fabric, they used crushers, ruffles, spinning wheels, spindles, self-spinning wheels, reels, reels, rams, warping machines, cross-weaving mills.

The local originality of all these instruments of labor and adaptations, if at all, manifested itself, then only in separate details that did not affect their general design. So, for example, seedlings differed only in the material from which they were made; flails from different regions of Russia - by the method of connecting the beat with the handle; spinning wheels - the size and ornamentation of the blade, where the tow was attached, etc. The uniformity of the tools of peasant labor was due to the generality of the technological process in which they were used throughout Russia. The variety of soil-cultivating tools was associated with the natural and climatic conditions and the farming system adopted in a particular area.

In most of Russia, the main arable tool was the plow - a tool with a high attachment of tractive power, well suited for working on light forest soils with an abundance of small stones, bushes and tree roots. The plow was used where the steam three-field farming system was widespread, in which one field was left “in a pair,” “fallow,” annually to restore soil fertility, and the other two were sown with winter and spring rye. In the central regions of European Russia, along with the plow, roe deer were known, which were used to raise nova, as well as to work on black earth and loamy soils. It had, like the plow, a high attachment of traction force, but differed in the presence of one share and a cutter instead of two plowshares typical for the plow.

The heavy chernozem soils of the steppe and forest-steppe provinces of Russia were plowed up using a plow - a tool with a low attachment of tractive power, with one share and a cutter. Harrows were used to loosen the soil after plowing, mixing layers and removing weeds. At the end of the plow or roe deer, wooden harrows with wooden teeth were used, and after the plow, harrows (wooden or metal) with metal teeth were used. It should be noted that all tillage implements had many design options, which is explained by the desire of the peasants to make them more perfect, better adapted to the soils and climate of the area where they were used.

Each version of this or that tool had its own name, which either reflected the features of its device, or indicated the place of its existence, for example: a two-sided plow, one-sided plow, a plow with flews, Kostroma roe deer, Yaroslavl roe deer, Kurashimka, Chegandinka, Russian plow , Little Russian plow, etc. Livestock raising was closely connected with agriculture, which gave the economy draft power and fertilizers. In this section, the reader will find information about tools for caring for animals - these are tools for the preparation of forage (primarily hay) and for grazing. The set of tools required for hay preparation included a scythe, rake and pitchfork. Each of these guns also had a variety of design options.

So, for mowing grass in flooded meadows, they used both a stand-up braid and a kosugorbush, on marshy or stony lands - mainly a pink salmon braid; a rake with a straight block was used for tedding hay, and with a slightly rounded one to collect it; stacking was carried out using wooden three-toothed or four-pronged forks, depending on the height of the stack and the volume of the raised heap - with long or, conversely, relatively short handles. Grazing implements: whip, batog stick, signal horn, as a rule, were the characteristic attributes of a shepherd. When grazing livestock without a shepherd, various kinds of neck bells were used, which rang, dangling around the animal's neck, and allowed the owner to quickly find it.

The implements of labor necessary for the economy were made in Russian factories and handicraft workshops, of which there were many in Russia in the 19th - early 20th centuries. The peasants bought them at fairs, bazaars, or ordered them directly from artisans. First of all, this concerned tools, the manufacture of which was not possible at home. Tools and devices, simpler in design, did not require special knowledge, a lot of effort and time, were made by the peasants themselves. The tools used in the peasant economy were created and improved throughout the centuries-old history of the Russian people. They were constructively thought out, well adapted to various natural and climatic conditions. We can say with confidence that for their time they were quite perfect and only technical progress from the second half of the 19th century. gradually ousted them from the economic life of the Russian peasant.