This have not happened before!

70% discount on continuing education courses

The number of discounted seats is limited!

Training takes place in absentia directly on the site of the "Infourok" project

(The license for educational activities No. 5201 was issued by Infourok LLC on May 20, 2016 for an unlimited period).

|

|

1 in 20

Description of the presentation by individual slides:

Slide No. 1

Slide Description:

PRESENTATION - RESEARCH OF AGRICULTURAL EQUIPMENT “WITHOUT WORKING EQUIPMENT - AND NO THERE, AND NO HERE” THE WORK WAS PERFORMED BY CLASS 5 STUDENT LIZA BOLSHAKOVA, 11 YEARS OLD LEADER - TEACHER N.V. BOLSHAKOVA UVAROVO 2013

Slide No. 2

Slide Description:

In factory labor there is something that deadens the soul, in peasant labor it is life-giving. The peasant lives by his labor, work is the whole meaning of his life. In the popular environment, the idea that work is blessed by God has taken root. No wonder the worker is addressed with the words: "God help!", "God help". In response, we hear: "On God, do not do it yourself." Here is the peasant and does not go wrong. Works from morning till night. His work is hard. So there was and is facing the peasant one eternal question: "And how to do it so that the work is done faster, with the least expenditure of effort, and even get a richer harvest, and feed more cattle." Here, too, the peasant did not fail! How many different tools of labor agriculture made! From the most primitive manual to self-propelled harvesters. My life is inextricably linked with agriculture, animal husbandry. I know firsthand how many of the peasant's tools are used, which make his life easier, because my grandmother worked on a collective farm all her life, my father and mother are engaged in housework: they plant a garden, potatoes, sow rye and oats, feed a cow, sheep, chickens ... I often listen to my grandmother's stories about how they used to work. All their tools were hand-made, it is good if there was a horse in the tree. How much strength and health my grandmother gave to work in her native land! The people have put together many proverbs and sayings about the implements of agricultural labor. This shows how important they are for the peasant. In my work, I will show what tools and tools were used and are used by people living in our region. And you will see how they improve and make life easier for a person working on the earth.

Slide No. 3

Slide Description:

Agricultural tools. The word "agriculture" speaks for itself - to make land, that is, to cultivate it to preserve and increase soil fertility. Along with the food obtained by primitive hunting for wild animals and birds, primitive man used fruits, berries, nuts from trees, grains and fruits of herbaceous vegetation, their edible roots, tubers, bulbs and leaves for food. From the ground, he extracted larvae, insects and worms. The number of people gradually grew, their need for food obtained by gathering and hunting increased. Digging tubers and roots out of the ground, primitive man noticed that new plants of the same kind grow from crumbled seeds or from tubers remaining in the loosened soil, and they are more powerful and with a large number of large fruits or grains. Such an observation led a person to the idea to deliberately loosen the earth and lay seeds in the loosened layer. Over time, people learned to plant seeds not in a heap, but scattered or in a furrow. At the same time, a certain plot of land was formed, the cultivation of which became a systematic matter, and the stick, which previously only knocked fruits from trees or dug up the edible roots of wild plants, turned into the first instrument of agricultural labor on Earth.

Slide No. 4

Slide Description:

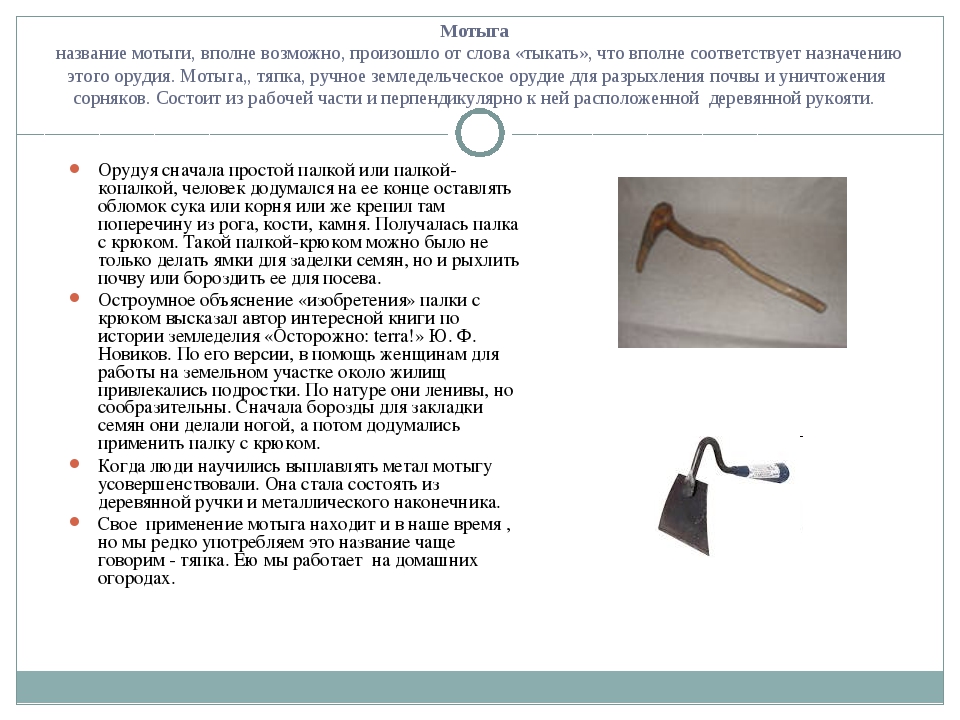

Hoe The name of the hoe, quite possibly, comes from the word "poke", which is quite consistent with the purpose of this tool. Hoe, hoe, hand-held agricultural tool for loosening the soil and killing weeds. Consists of a working part and a wooden handle located perpendicular to it. Wielding at first a simple stick or a digging stick, a person thought of leaving a piece of a bitch or root at its end, or he fastened a crossbar made of horn, bone, or stone there. It turned out a stick with a hook. With such a stick-hook it was possible not only to make holes for planting seeds, but also to loosen the soil or furrow it for sowing. An ingenious explanation of the "invention" of a stick with a hook was expressed by the author of an interesting book on the history of agriculture "Beware: terra!" Yu. F. Novikov. According to him, teenagers were involved in helping women to work on the land plot near the dwellings. They are lazy by nature, but smart. First, they made furrows for planting seeds with their feet, and then they thought of using a stick with a hook. When people learned to smelt metal, the hoe was improved. It began to consist of a wooden handle and a metal tip. The hoe finds its use in our time, but we rarely use this name more often say - hoe. We work with her in home gardens.

Slide No. 5

Slide Description:

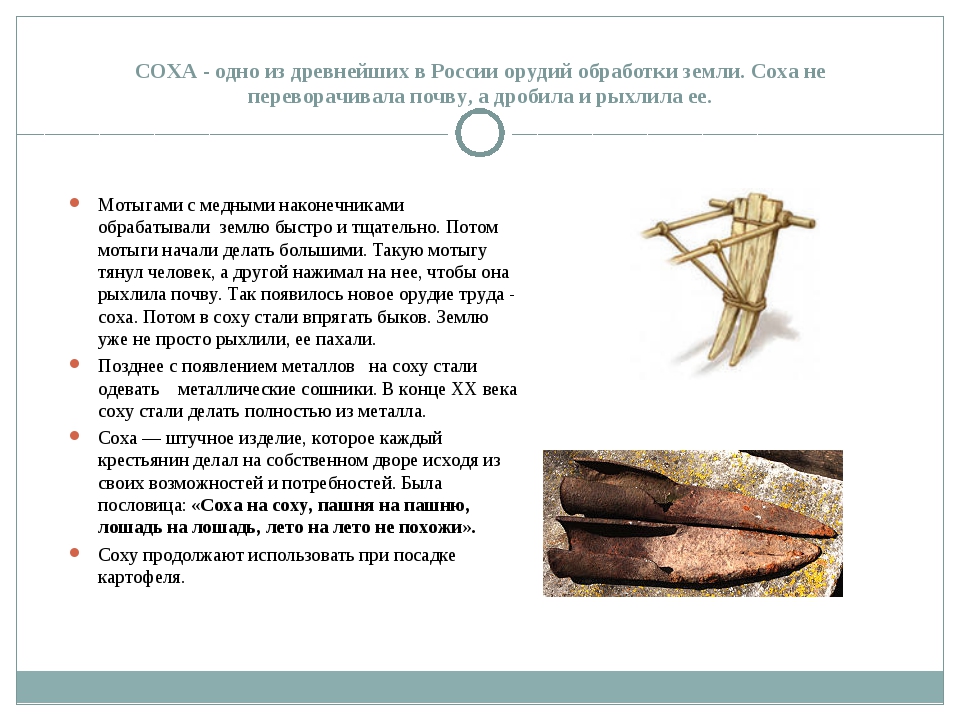

SOKHA is one of the oldest land cultivation tools in Russia. The plow did not turn the soil, but crushed and loosened it. The copper-tipped hoes worked the land quickly and carefully. Then the hoes started making them big. Such a hoe was pulled by a person, and another pressed on it so that it loosened the soil. This is how a new tool of labor appeared - the plow. Then they began to harness the bulls to the plow. The land was no longer simply loosened, it was plowed. Later, with the advent of metals on the plow, they began to wear metal openers. At the end of the 20th century, plows began to be made entirely of metal. Sokha is a piece product that each peasant made in his own yard based on his capabilities and needs. There was a proverb: "A plow for a plow, arable land for arable land, a horse for a horse, summer does not look like summer." The plow continues to be used when planting potatoes.

Slide No. 6

Slide Description:

The plow is an agricultural tool for basic soil cultivation And when sharp copper tips were attached to the plow, it became a plow. The strength of the bulls, the weight of plows and plows, the sharpness of copper sickles saved the strength of the farmers. The main task of the plow is to turn the top layer of the earth. Plowing reduces the number of weeds, makes the soil softer and more pliable, and facilitates further seeding. Later, the plow was made of metals. Initially, the plows were pulled by the people themselves, then by oxen, and even later by horses. At present, a tractor is pulling into the plow. The inhabitants of our settlement use 2 types of plows: horse and tractor. The plow is used as an emblem of agriculture and as a symbol of new life. The plow was depicted on Soviet 1 ruble and fifty kopeck coins in the 1920s. Tractor plow And as soon as spring comes, dad will hook his powerful assistant to the tractor and quickly plow the land. Horse plow

Slide No. 7

Slide Description:

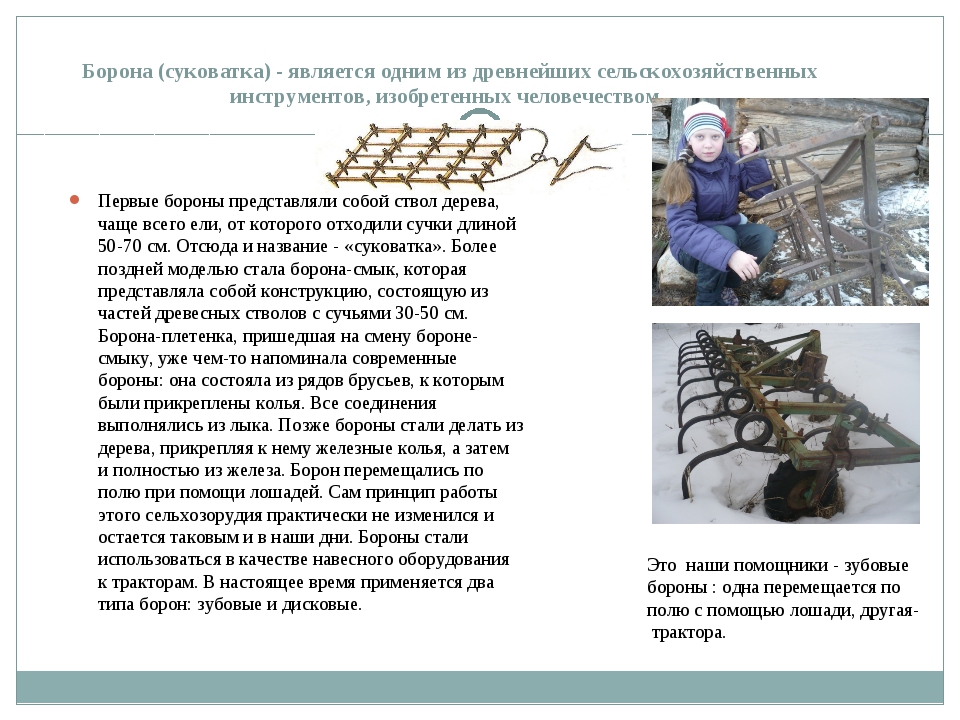

Harrow (bitch) - is one of the oldest agricultural tools invented by mankind. The first harrows were a tree trunk, most often spruce, from which twigs 50-70 cm long emerged. Hence the name - "knotty". A later model was the bow harrow, which was a structure consisting of parts of tree trunks with branches of 30-50 cm. The braided harrow, which replaced the bow harrow, was already somewhat reminiscent of modern harrows: it consisted of rows of beams, to which the stakes were attached. All connections were made from bast. Later, the harrows began to be made of wood, attaching iron stakes to it, and then completely of iron. Harrows moved across the field with the help of horses. The very principle of operation of this agricultural equipment has practically not changed and remains so today. Harrows began to be used as attachments to tractors. Currently, two types of harrows are used: tooth and disc harrows. These are our assistants - tooth harrows: one moves across the field with the help of a horse, the other with a tractor.

Slide No. 8

Slide Description:

The seeder is a machine for evenly sowing seeds into the soil. Before the invention of the seeder, sowing of grain was done by manually spreading seeds and then harrowing. Under this system, a lot of grain was consumed, it was distributed unevenly over the ground, the seedlings were uncooperative, and the farmer was very tired. It was only in the 19th and early 20th centuries that an iron seeder appeared, consisting of a pair of seed boxes, a primitive seed tube, openers that form grooves for seeds in the ground, and organs that filled the resulting grooves and level the ground. They were dragged by a horse. The seeders became more complicated, improved and modified. Now they are being dragged along strong tractors... a traditional sowing basket (a school museum exhibit); and a modern seeder. This universal seeder is used by Dad for spreading fertilizer and sowing grain.

Slide No. 9

Slide Description:

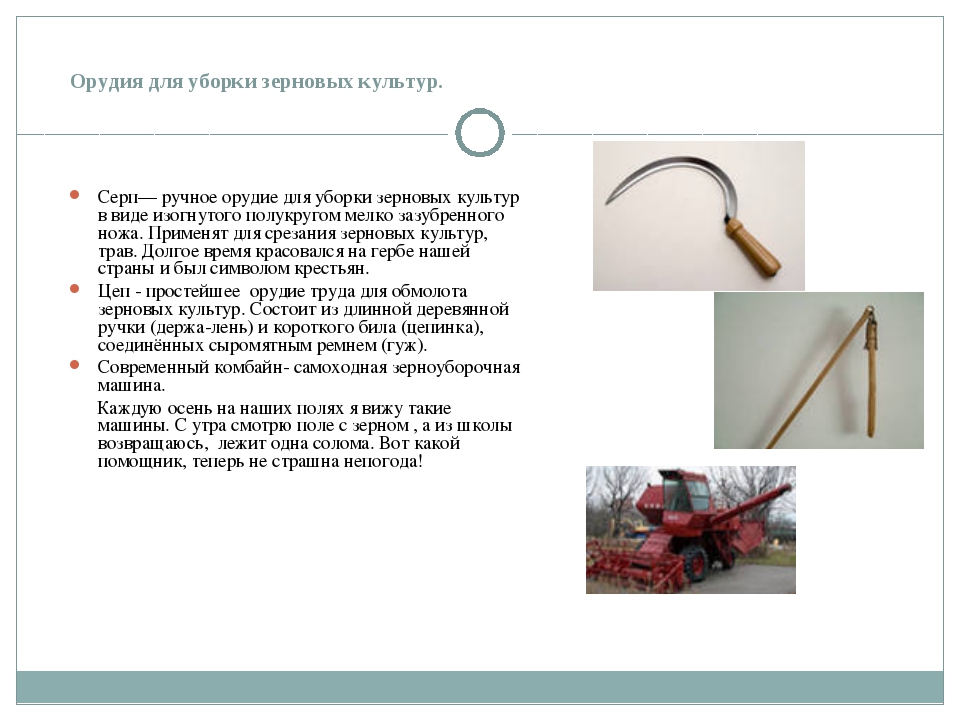

Equipment for harvesting grain crops. The sickle is a hand tool for harvesting grain crops in the form of a finely serrated knife curved in a semicircle. Used for cutting grain crops, grasses. For a long time it adorned the coat of arms of our country and was a symbol of the peasants. A chain is the simplest tool for threshing grain crops. Consists of a long wooden handle (holding-lazy) and a short hammer (chain), connected by a rawhide belt (gug). A modern combine is a self-propelled grain harvester. Every autumn I see such machines in our fields. In the morning I look at a field with grain, and I return from school, there is only straw. What an assistant, now the weather is not terrible!

Slide No. 10

Slide Description:

Livestock breeders' tools. A long time ago, when - it is not known for sure, returning from an unsuccessful hunt, under the grumbling of a hungry wife and stomach, a primitive man thought: "And maybe what to run through the forests and fields for game, make it always at hand?" This is how the first prerequisites for the conduct of domestic livestock appeared. Since then, humanity has created an entire industry to meet its needs for meat, milk, skin, etc. Huge complexes for raising cows, pigs, chickens, sheep and rabbits have been built. In our settlement, every house has pets. They are all living things and require care and food. And here again tools of labor come to the aid of man. On a rural farm: my grandmother's workplace In our yard

Slide No. 11

Slide Description:

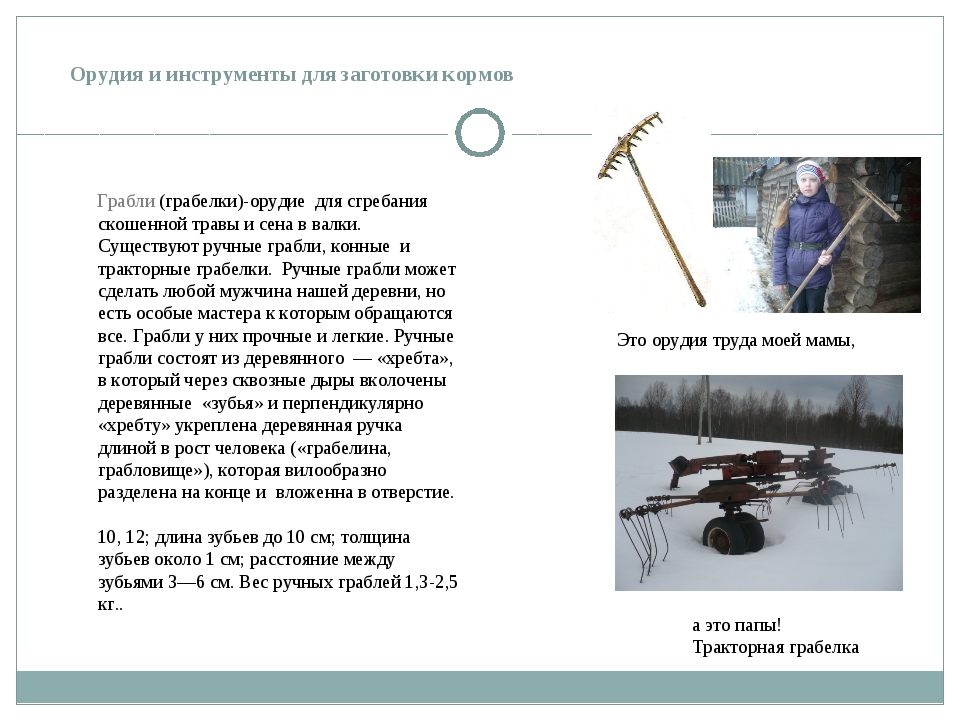

Tools and tools for harvesting forage Rakes (rakes) - a tool for raking cut grass and hay into swaths. There are hand rakes, horse rakes and tractor rakes. Any man in our village can make a hand rake, but there are special masters to whom everyone turns. Their rake is strong and light. A hand rake consists of a wooden “ridge”, into which wooden “teeth” are driven through holes through the holes, and a human-sized wooden handle (“rake, rake”) is strengthened perpendicular to the “ridge”, which is forked at the end and inserted into the hole. The number of teeth in a hand rake is usually 8, 10, 12; length of teeth up to 10 cm; the thickness of the teeth is about 1 cm; the distance between the teeth is 3-6 cm. The weight of the hand rake is 1.3-2.5 kg .. These are the tools of my mother's, and these are my father's! Tractor rake

Slide No. 12

Slide Description:

Fork is an agricultural portable hand tool used by farmers in agriculture for loading and unloading hay and other agricultural products. The pitchfork is an indispensable tool in the household. You can put the hay into a heap, you sweep it into a haystack, you can do the cleaning in the barn, and you are an irreplaceable assistant in the garden. The first were wooden pitchforks. Their main advantage was weight, they were light. But the tree is fragile and the pitchfork did not last long. Then a pitchfork appeared in which the nozzle (handle) is made of wood, and the spear is made of metal. These pitchforks are durable and serve the owner for a long time. And now in every rural house a pitchfork is an irreplaceable tool of labor.

Slide No. 13

Slide Description:

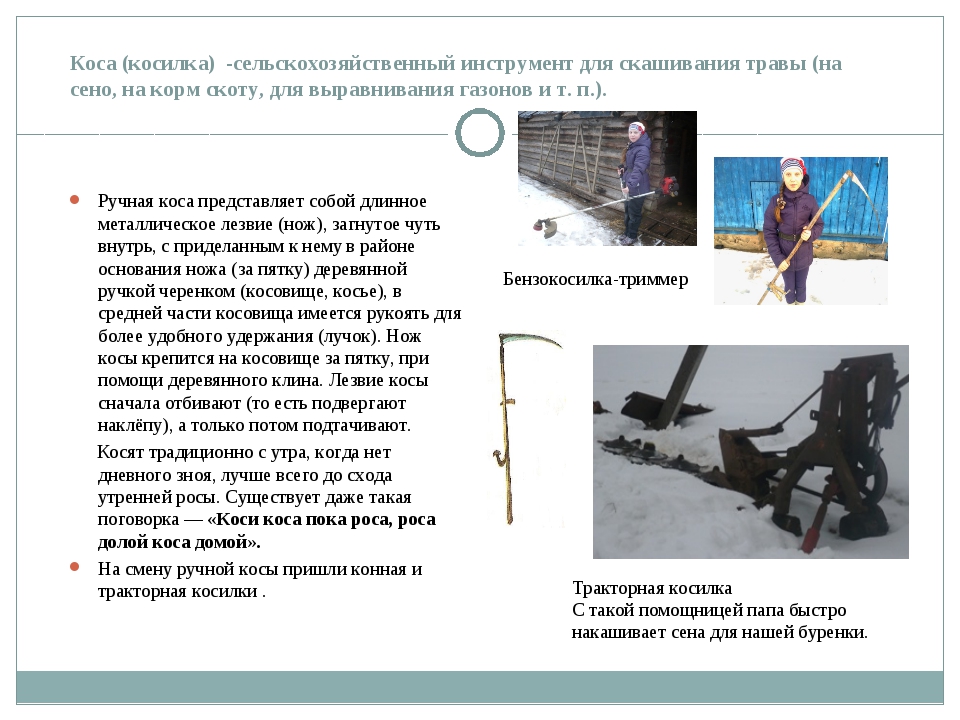

A scythe (mower) is an agricultural tool for mowing grass (for hay, for fodder for livestock, for leveling lawns, etc.). The hand scythe is a long metal blade (knife), bent slightly inward, with a wooden handle attached to it near the base of the knife (behind the heel) (kosovishche, mowing), in the middle of the kosovishche there is a handle for more comfortable holding (bow). The scythe knife is attached to the braid by the heel using a wooden wedge. The blade of the scythe is first beaten off (that is, subjected to work hardening), and only then it is sharpened. Traditionally, they mow in the morning, when there is no heat of the day, preferably before the morning dew melts. There is even such a saying - "Mow the spit while the dew is, the dew is off the spit home." The hand scythe was replaced by horse and tractor mowers. Tractor mower With such an assistant, dad quickly mows hay for our cow. Petrol trimmer

Slide No. 14

Slide Description:

Sheep shears Shearing sheep is a serious and laborious business. Sheep are sheared 2 times a year: in spring and autumn. Sheep should be sheared prior to feeding and drinking. Their coat should be dry during clipping. The very first tool for shearing sheep is hand scissors, they are very similar to ordinary shears, only in large sizes. Cutting with such a tool is difficult and time-consuming. And if you need to shear a whole flock of sheep? Therefore, they came up with scissors for shearing sheep, which are very similar to the machines used by hairdressers. Here mom will cut your hair and you will be beautiful! sheep clippers

Slide No. 15

Slide Description:

Spinning wheel (self-spinning wheel) - a tool for spinning threads. Spinning wheels come in different sizes, shapes, they are made of different types of wood, have a variety of styles. My grandmother also has a spinning wheel. The spinning wheel works like a bicycle. When your feet are on the pedals, the lever turns the shaft that turns the wheel. When the wheel rotates, the belt rotates the head, reel, or both. This rotation is transferred to the fiber and bunches it into the thread. People invented electric spinning wheels, but grandmother still prefers her old friend to self-spinning. She will spin yarn, and my mother will knit warm socks. My brother is learning grandma's craft, so the spinning wheels have changed

Slide No. 16

Slide Description:

Milking machines for cows For a long time, human hands were the main tool for milking cows. My grandmother milked the cows on the farm by hand for many years. This milking is called manual. This is very hard work. Before milking, hands are washed with soap and a clean robe is put on. Before milking a cow, it is recommended to tie her tail, examine the udder, teats and rinse them thoroughly. The udder of the cow is washed from a bucket with warm water; Then wipe the udder dry with a towel. In manual milking, they sit on a bench, located on the right side along the cow's path. The milker must love the animal, treat it kindly. The livestock population increased, and people could no longer cope with such volumes of labor, and then milking machines that run on electricity came to the rescue. This greatly facilitated the work of the milkmaid. In our village there is a cattle farm where dairy cows are raised. Thanks to milking machines, one milkmaid is able to milk up to 30 cows per milking. During milking

Slide No. 17

Slide Description:

Pulling power From time immemorial, the horse has helped people to manage the farm. The peasant has long used the horse in the farm as a pulling power. My grandmother said that they plowed, sowed, transported, mowed, rowed hay on her. And to this day, horses are needed by shepherds for riding when grazing animals, as vehicle off-road, with snow drifts, as well as for household needs on a personal backyard. In the household, we use a horse for driving furrows with potatoes, plowing a vegetable garden. Of course, a horse is not a substitute for a farm.

Slide No. 18

Slide Description:

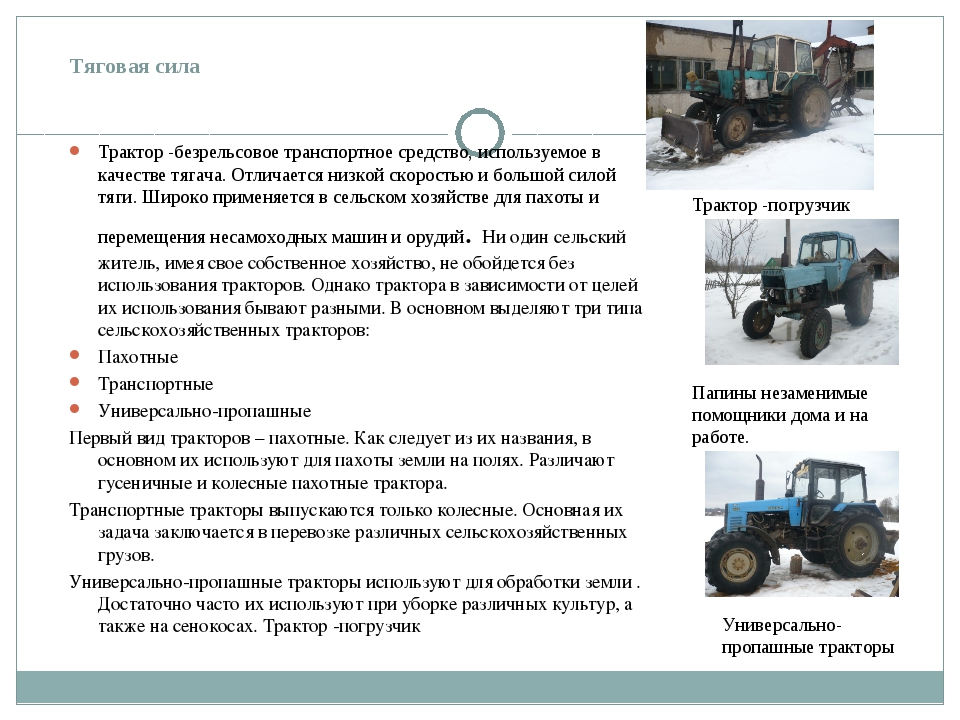

Tractive force Tractor is a trackless vehicle used as a tractor. It features low speed and high traction. It is widely used in agriculture for plowing and moving non-self-propelled machines and implements. Not a single villager, having his own farm, can do without the use of tractors. However, tractors, depending on the purpose of their use, are different. Basically, there are three types of agricultural tractors: Arable Transport Universal row-crop The first type of tractors is arable. As their name suggests, they are mainly used for plowing land in fields. A distinction is made between tracked and wheeled arable tractors. Transport tractors are produced only with wheels. Their main task is to transport various agricultural goods. Universal row-crop tractors are used to cultivate the land. They are often used for harvesting various crops, as well as for hayfields. Tractor-loader Daddy's irreplaceable helpers at home and at work. Universal row-crop tractors Loader tractor

Slide No. 19

Slide Description:

In my work, I do not put an end, but put an ellipsis, because a Man uses tools of labor constantly and in all spheres of his life, creating from them and with the help of them the world of permanent things around him. Any person tries to improve his life, to make his work easier. And here helpers come to his aid - tools of labor. And while the peasant is faced with the question: "How to make it so that the work is done faster, with the least expenditure of effort, and even get a richer harvest, and feed more cattle." he will look for more perfect helpers, of which we now do not even suspect. Because without tools, we are neither there, nor here! The guys of our school during the spring work on the training and experimental site and our irreplaceable assistant - the tractor Mitya.

Slide No. 20

Slide Description:

conclusion In my presentation, I talked about how our peasant created and used different tools to make the work easier? The physical severity of this labor is not the biggest problem. It is much more important that the work of the peasant is held in high esteem, that it is appreciated and respected in society. Thanks for attention!!!

To download the material, enter your email, indicate who you are, and click

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists using the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Arable implements and their evolution

The word "agriculture" speaks for itself - to make the land, that is, to cultivate it to preserve and increase soil fertility. The realization of this great truth came to man as a result of his centuries-old evolution. The roots of agriculture go back to the Neolithic era.

Along with the food obtained by primitive hunting for wild animals and birds, primitive man used fruits, berries, nuts from trees, grains and fruits of herbaceous vegetation, their edible roots, tubers, bulbs and leaves for food. From the ground, he extracted larvae, insects and worms. This period in the development of human society in historical science was called the period of gathering.

The number of people gradually grew, their need for food obtained by gathering and hunting increased. Then people began to look for other sources of food or migrate to new habitats.

Digging tubers and roots out of the ground, primitive man noticed that new plants of the same kind grow from crumbled seeds or from tubers remaining in the loosened earth, and they are more powerful and with a large number of large fruits or grains. Such an observation led a person to the idea to deliberately loosen the earth and lay seeds in the loosened layer. Over time, people learned to plant seeds not in a heap, but scattered or in a furrow. At the same time, a certain plot of land was formed, the cultivation of which became a systematic matter, and the stick, which previously only knocked fruits from trees or dug up the edible roots of wild plants, turned into the first instrument of agricultural labor on Earth. Not so long ago, travelers and ethnographic scientists came across such tools from some backward tribes in Africa, Asia and America.

The period when a person with the help of a stick began to loosen the ground and deliberately plant seeds or tubers in it, in order to get a harvest from them later, is considered to be the beginning, the birth of agriculture.

At the dawn of agriculture, primitive man, loosening the earth, sought only one goal that he understood - to close up the seeds. But over time, he realized that by cultivating the land, you can destroy unnecessary plants and thereby increase the collection of fruits. Realizing this, the person began to cultivate the soil consciously. For better loosening and greater labor productivity, he more and more improved the tool for tillage.

To make it easier to press the stick into the ground, a transverse branch was left on it on the side, or some kind of crossbar was specially attached to which the digger, helping himself, pressed with his foot. Such a device was especially necessary for working hard or soddy soil. Also, for the convenience of work, a crossbar was made at the top of the stick, like the one that can sometimes be seen at the spades. Such a tool found by archaeologists was named "digging stick" or "digging stick".

Still, it was difficult to loosen the soil with a stick, even with tools. And then the primitive farmers began to expand the lower end of the stick. At first it looked like a paddle, and then gradually turned into a shovel. Of course, such a shovel, made with stone tools, was very crude and only vaguely resembled a modern one. It was hard to work with her. A new improvement helped to facilitate the work and make it more productive: a wide animal bone or a plate from a tortoise shell was attached to a stick as a blade. With such a tool, it was already possible not only to pick the ground, but also to wrap its layer.

Wielding at first a simple stick or a digging stick, a person thought of leaving a piece of a bitch or root at its end, or he fastened a crossbar made of horn, bone, or stone there. It turned out a stick with a hook. With such a stick-hook it was possible not only to make holes for planting seeds, but also to loosen the soil or furrow it for sowing.

An ingenious explanation of the "invention" of a stick with a hook was expressed by the author of an interesting book on the history of agriculture "Beware: terra!" Yu. F. Novikov. According to him, teenagers were involved in helping women to work on the land plot near the dwellings. They are lazy by nature, but smart. First, they made furrows for planting seeds with their feet, and then they thought of using a stick with a hook.

In the future, this primitive tool was improved. A plate made of improvised strong materials was attached to the bitch at the end of the stick with fibrous plants, tendons or leather straps. By modern definition, such a tool can already be called a hoe. Scientists have found it in many places during excavations of the sites of ancient people of the Stone Age and, more recently, among tribes that were backward in their development, who did not yet know iron.

To facilitate the work, the hoe could be used in work by two people. One pulled her by the strap, while the other guided and held her in the ground. It was already a kind of team. In order to make it easier to hold the hoe in the ground, a handle-holder was attached to it at the top, or simply a tree-stick was picked up with an appropriate branch for this. Working with such a tool was already a kind of plowing, or, in any case, cutting furrows for planting tubers or sowing seeds. During the second pass, the "plowmen" filled the furrow with already laid seeds, and the next portion of seeds was laid in the new furrow that had formed. So, in essence, in our time, potatoes are planted using a plow and horse traction.

Initially, agriculture arose in places where there was fertile land and sufficient heat and moisture. The creation of certain types of tools by primitive people was also influenced by the density of the soil, its moisture and turf. Somewhere for a long time tools made entirely of wood were held, and somewhere immediately the working part of the tool was made of a stronger material. Somewhere it was more convenient to work with a hoe, and somewhere - a shovel.

Naturally, agriculture was born on our planet not in one, but in many places and far from at the same time. therefore primitive tools tillage were very diverse, what is said here about the evolution of these tools is only a general scheme.

The period of development of human society, when a hoe and a shovel were the main tools for tillage, is called the period of hoe farming by modern historical science. Only small areas could be mastered with tools of that time. They were located near or even inside the settlements. Often they were surrounded by hedges to protect them from wild animals. Thus, both in terms of cultivation tools and in areas of cultivated land, agriculture had the character of a garden type.

The period of hoe farming belongs to the Neolithic (New Stone Age) and to the primitive social system. Archaeologists find evidence of hoe farming in many places on all continents of our planet, except Australia. This period lasted for several millennia. In the regions of Africa and Asia, hoe and vegetable gardening has existed for at least five thousand years. In some tribes, especially backward in their development, the hoe as the main tool for tillage has been preserved to our times. On the territory of Russia, a similar type of agriculture lasted up to a thousand years in the central regions of the European part and up to two thousand - on the territory of modern Ukraine, Moldova, Transcaucasia and Central Asia. Scientists have established that the origin of agriculture on our planet began in the interfluve of the Tigris and Euphrates, on the banks of the Nile, in the south of Central Asia and on the American continent - on the territory of modern Mexico. The oldest material traces of agriculture known to science, dating back to the 7th - 6th millennia BC, were found in Palestine. In Western Europe, as established by archaeologists, agriculture arose in the V-VI millennium BC. There are many places on Earth where people began to engage in agriculture only one or two thousand years ago. And in Australia, the aborigines did not know agriculture until the arrival of Europeans there in the 17th century.

The emergence of agriculture was the most important historical turn in the development of mankind. Growing edible plants for himself, man has largely freed himself from the influence of the elemental forces of nature on his life and received more guarantees from starvation. Agriculture is truly the greatest achievement of humanity.

Farming provided not only the simple reproduction of wild plants. It changed the quality of these plants in the direction useful for humans. Yes, and people themselves, it pushed to the knowledge of the laws of nature and helped to create the whole economic basis for the development of civilization.

Cutting up virgin and, moreover, forest-covered land with primitive tools required great efforts. People did not abandon the hardened land plot, but used it in subsequent years. Thanks to this, they began to move from a nomadic lifestyle to a settled lifestyle, becoming more and more convinced that growing plants is a more reliable way of obtaining food than gathering and hunting, where much depends on random luck or failure. With the advent of agriculture, gathering and hunting gradually faded into the background.

The most rapid development of culture went on the territory of Asia Minor, Egypt and India, where, on the basis of gathering, in the transition period from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic, agriculture and cattle breeding began to arise. At the same time, agricultural and pastoral culture emerged in the territory of modern Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia. Almost all peoples have myths and legends, which say that the gods taught agriculture and in one way or another introduced them to arable implements.

Obviously, the first animals that man tamed for work in agriculture were a bull and a cow. This is evidenced by archaeological finds, as well as the cults of ancient farmers. So, during the excavation of human sites in Asia and Europe, on objects and rock carvings found there, dating back to the 7th-6th millennia BC, researchers found images of bulls or cows in a team. In the 4th millennium, written myths appeared, testifying to the cult of the bull.

When agriculture developed significantly, the leadership in it passed to men and the improvement of soil cultivation tools went at a faster pace.

The first draft plowing implement appeared at the end of the 5th - beginning of the 4th millennium BC in the state of Sumer. On the territory of ancient Sumer, archaeologists have found clay tablets dating back to the 4th millennium BC, with drawings of agricultural implements and a record of the whole literary work, a poem reproducing an interesting debate between a hoe and a plow. The poem begins with the hoe boasting about the work she does. In response, the plow praises its merits. To resolve this dispute, the hoe and plow turned to the god Enlil. The "wise god" settled the dispute in favor of the hoe. Probably, this decision was led by the fact that the then plow was very imperfect.

In historical, artistic and literature translated from ancient languages, the primitive arable tool of the ancient inhabitants of the earth is usually called a plow. From the point of view of the modern agronomic concept, this is completely wrong. This ancient plow had neither a blade, nor a plowshare, in the old days called a runner, just those parts that define the concept of "plow".

The plowing tool of the Sumerians, Babylonians, Egyptians and other ancient peoples was a thick tree - a longitudinal bar. For such a bar, a tree with oppositely directed branches was originally selected. One of the bitches went up and served as a handle-holder, and the other down, he was the actual working body. A yoke was attached to the bar in front, into which oxen were harnessed, or even people - slaves.

If there was no natural tree with the necessary branches, then the corresponding pieces of wood were attached to the timber, one of which was directed into the ground, and the other served as a holder. At best, a pair of handles were attached for both hands. It was easier to work that way.

The entire tool was made of wood, and it was only with the development of iron production that an iron tip was attached to the end of the working body.

Until about the 14th century, the peasants in Russia had exactly the same weapon. A similar tool, but under the name omach, was the main tool for tillage among the peoples of our Central Asia until collectivization.

The Great Soviet Encyclopedia (3rd edition) Ralo calls an agricultural tool similar in type to a primitive plow. One can agree with this definition, but one must only bear in mind that the swath could only plow, loosen the ground, without performing the main action of the plow - to wrap the layer.

Summing up the development of primitive agricultural implements, you can schematically represent their development. At first there was a primitive stick, then a stump of a bitch was left on the side of the stick or some kind of crossbar was attached to it, pressing on which with the foot made it easier to press the stick into the ground; over time, the stick began to be processed with a stone ax to give it the shape of first an oar, and then a shovel, which increased the productivity of the primitive farmer and made it possible not only to loosen, but also to wrap a layer of soil; the next stage in the evolution of agricultural implements is the use of any plate made of flat animal bone, a tortoise shell, a relatively flat shell as a shovel blade, which facilitated the loosening and turning of the layer; a sturdy plate began to be attached to the stick at a right angle, such a tool was the prototype of a hoe (hoes, hoes, hoes, ketmen); the use of tamed animals in agriculture made it possible to create a powerful, sturdy tool, similar to the one that served the peasants of Russia for a long time under the name "ralo".

The path from stick to ral, like the development of human society, ran through many millennia.

In their cultural development, the most ancient civilizations of the Sumerians, Babylonians, Egyptians eventually gave way to the Greeks and Romans. These peoples far surpassed the more ancient civilizations in military affairs, architecture, art, medicine, philosophy, but for a long time they did not make any progress in agriculture. Their agriculture was dominated by slave labor. Numerous wars of conquest waged by the Greeks and especially the Romans allowed them to bring a huge number of prisoners to their homeland. These prisoners were then sold as slaves to landowners. Using cheap, essentially free labor of slaves, the owners were not interested in improving the tools of agriculture. Therefore, for a long time in Greece, and then in Rome, the primitive plow of the ral type remained the main tool for tillage. The hoe was also in great, if not more, move.

True, the ancient Greeks, along with the usual ral, had a kind of plow with a wooden blade, but it did not yet have a runner important for the plow. This Greek tool did not leave a noticeable trace in the history of agriculture. The merit of the invention of the present plow belongs to the Romans, but this happened only in the last period of the existence of the Roman Empire.

The impetus for the invention of the plow with a blade and a runner was the conquest of Gaul by the Romans (the territory of modern France, Belgium, Luxembourg, parts of the Netherlands and Switzerland), where at that time there were many lands untouched by cultivation. These lands were handed out to Roman soldiers for military merit, primarily, of course, to military leaders. It was extremely difficult to raise the virgin lands by ral. Their development required and led to the invention of a tool suitable for plowing newly developed land. This is how a plowing tool appeared, which could rightly be called a plow, although at first all its parts were made of wood.

In the Roman plow, the beam (the part to which all the working parts and plow handles are attached) rested on the front end with two wooden wheels. A drawbar with a yoke was attached to the front end, into which bulls or slaves were harnessed. With the help of the front end, it became possible to adjust the plowing depth and seam engagement width. With such a plow it was quite possible to plow new lands, and the old arable lands were cultivated better and easier. The outstanding Soviet scientist, the founder of the theory of agricultural machines Vasily Prokhorovich Goryachkin wrote in his work "Towards the History of the Plow": "People realized that under the rough, clumsy form of a primitive tool hides what helped a person to free himself from subjection to his nature, and surrounded this modest tool a halo of high veneration and even holiness. The Romans used a plow to make a furrow that served as the inviolable border of cities. The Chinese emperor made the first furrow himself every year. "

With the fall of the Roman Empire and the onset of the dark Middle Ages, many of the cultural and technical achievements of the Romans were forgotten. The same fate befell the Roman plow. It was completely forgotten, and many centuries later it had to be “reinvented”. This happened only in the middle of the 17th century in Belgium and Holland. It is possible that it was the Roman plow that served as a design model. Similar to the Belgian and Dutch, plows were also made in other European countries, and they served the peasants of these countries for almost two centuries without any special changes. Creation proceeded somewhat differently arable implements in Ancient Russia.

Unfortunately, we have almost no written evidence of agriculture since the inception of the Russian state. The only document of the history of those times is the annals. The chroniclers, on the other hand, focused on stories about the struggle with external enemies, about the construction of fortress cities, about the life and work of princes, rulers of the church, etc. them hunger.

Using the scanty chronicle data, archaeological finds and the works of historians, one can still imagine how agriculture developed in Russia at that time, how much work, perseverance and resourcefulness our distant ancestors had to use, mastering virgin lands with the help of primitive means of production.

Depending on the natural conditions in the southern and northern regions, different methods of soil cultivation developed.

In the 6th century in Russia, in the southern steppe regions, a fallow land was formed, and later, as a result of a reduction in the period of a fallow, a transitional farming system; in the northern forest regions - slash and burn.

Under the fallow system, the plowed virgin steppe area was used for sowing for three to five years or more, until natural fertility was depleted. Then this site was excluded from processing for 20 years or more, and a new one was plowed up instead. The abandoned area was overgrown with grass, its fertility was gradually restored, after which it was processed again. The relocation system differed from the fallow one in that the period of “rest” of the land was reduced to 10-8 years, and the land “resting” in this way was called the relocation.

With the growth of the population, the need for food products increased. This prompted farmers to plow up more and more virgin lands and reduce the time of fallow land. So, the deposit first passed into the fallow, which eventually came down to one year called "steam".

In the northern forest regions, for the cultivation of crops, it was necessary to develop forest lands. The so-called slash-and-burn farming system has developed here. The forest was uprooted, burned, and the resulting ash served as a good fertilizer. Mainly rye and flax were sown. The lands obtained in this way, in the first years, provided relatively high yields, then the soil lost its fertility, yields sharply decreased, and farmers were forced to clear a new plot for sowing.

The development of the land occupied by the forest cost a lot of labor. In addition, the growth of the population and therefore the demand for food required more and more arable land. Then the developed areas were no longer thrown into a new afforestation, and they began to be left for one year for "rest" as steam. Both in the forest regions and in the steppe regions, first a two-field and then a three-field system of agriculture developed.

The transition from the fallow and slash systems to the steam system was an indisputable progress in agriculture, since at the same time the cultivated area was much increased, the land was used more productively. Thus, natural and economic conditions influenced the farming systems. They, in turn, demanded changes in the designs of agricultural implements.

During the formation of Kievan Rus, the main arable tool was a ralo, which was a cut of an oak or hornbeam tree with a branch pointed at the end - the actual working body - and a grip handle. The more advanced raul had two handles. Over time, an iron tip was put on a pointed branch - a head with a small triangular blade. This made the work easier, but even in this form the ral could only cut through the sod layer of the soil and only slightly loosen it. Meanwhile, when plowing virgin and fallow lands, it was necessary to cut the layer and, if possible, turn it over. This, to some extent, was achieved by making the blade of the shaft wider and placing it with some inclination to the side, and not strictly vertically. The appearance of such a handset was an important technical innovation in medieval Russia. Over time, it was transformed into a ploughshare.

Following the narylnik, the farmers created a device for dumping a layer in the form of a wooden board, and then - a cresol - a massive knife with which a layer of earth was cut off.

Tools of this type include the steppe "Little Russian" plow - saban. It was a bulky, heavy weapon, almost three meters long. With the exception of the ploughshare, the saban, including the blade, was entirely made of wood. They harnessed to the saban from 2 to 6 horses or 4-8 bulls. The positive thing about this tool was that it wrapped the layer well enough.

The main design feature of the Saban was that it had a horizontal wooden runner. From this, some researchers make the assumption that the word "plow" comes from the word "snake". In addition, in the Czech and Serbian languages, the word plow is pronounced "plaz", in Polish - "ploz" and "pluz". VP Goryachkin in his article "On the history of the plow", referring to Professor Garkena, noted that the word "plow" comes from the Slavic word "pluti" (plauti, float). All these words are close in meaning.

At the time of the settlement of the German colonists in Ukraine, they had so-called bookers. Bukker is an aggregate of three to five furrow plows and seeders. He combined shallow (12-14 cm) plowing and sowing. The seeds fell into the plow furrow and were immediately covered with a layer of soil. From the German colonists, the booker passed to the Ukrainian farmers of the former Yekaterinoslav and other neighboring provinces. Depending on the number of plowshares, the bukker required harnessing from 4 to 6 bulls or horses. Russian scientists P.A.Kostychev, K.A.Timiryazev, V.R. Williams sharply condemned the work of the booker for small-scale plowing. Nevertheless, in some places in Ukraine, bookers survived until collectivization.

In the northern forest regions, where the slash farming system was widespread, the improvement of arable tools went in a different way. Here, after deforestation and burning of the forest, stumps and roots remained, there were many stones and large boulders left over from the ice age. It was impossible to cultivate such land with a heavy tool with a skid. Therefore, the researchers believe that the farmers of these places from ancient times and for a long time used a non-moldboard rally to cultivate the cut, but, obviously, not only them. The peasants of the northern and central regions of Russia before the revolution used a plow, a tool that was well known to the older generation, in tillage. Some researchers believe that the plow also originated from the Rahl, but other plow genealogy is from the so-called knot.

Sukovatka is the most primitive tool used in very ancient times for tillage on undercutting. A knot was made from a piece of the top of a spruce about 3 meters long. On the main trunk of the section, lateral 50-70 cm branches were left. A horse pulled such a weapon by a rope tied to its top. Sukovatka easily jumped over all the obstacles on the undercut, with multiple passes loosened the soil a little and covered up the seeds sown at random. Some scientists consider it to be the predecessor of the plow.

Linguistics also speaks for the hypothesis of the origin of the plow from the ral. In the old days, a plow was called any branch, twig or tree ending in a bifurcation. According to V. Dal, originally a plow was called a pole, a pole, a solid wood bifurcated at the end. Hence - rassokha, fry, plow. The basis of the plow construction is a wooden plate bifurcated from top to bottom - rassokha. If we discard "ras-", then we get "plow". It is possible that some kind of fork with a forked end was the predecessor of the plow. Also encyclopedic Dictionary Brockhaus and Efron testifies that in the old days the plow was called ral, and only from the XIV century the word “ralo” was supplanted by the word “plow”.

Even in ancient times, as recorded in the earliest works on agriculture, by cultivating the soil, people tried to solve certain problems: to loosen the soil as best and deeply as possible before sowing; cover the top sprayed soil layer, as well as fertilizers, sod, crop residues and loose weed seeds; destroy weeds and level the surface of the field.

Throughout the entire history of agriculture, these tasks have not essentially changed and were only supplemented by new ones.

In the recommendations of many agricultural scientists, instructions were invariably given to loosen the soil as much as possible and to the greatest possible depth with the obligatory rotation of the seam. Even Tsar Peter the Great had a hand in this. In one of his decrees, he ordered the farmers to plow "much and gently", that is, deeply and well loosening the layer of soil.

But at the end of the century before last, what seemed to be an immutable truth - the need for plow tillage, was first questioned. And during the 20th century, this revision of the foundations of agriculture has already acquired the form of a theory, firmly supported by practice. The reason for the revision of traditional tillage was the disastrous consequences of maximum loosening and turnover of the soil layer. The sad experience of the USA and Canada is especially indicative in this respect. Here, in the 30s of the XX century, the destructive process of wind erosion covered a huge area - over 40 million hectares. Farmers experienced a similar disaster in our country: in the North Caucasus, in the Volga region, in the virgin lands of Kazakhstan and Siberia.

The first person to suggest plowing in Russia without turnover was I. Ye. Ovsinsky. He tried to introduce methods of tillage without the use of a plow. In the Soviet Union, shallow tillage was recommended by Academician N. M. Tulaykov. The well-known innovator of agriculture, honorary academician of VASKhNIL TS Maltsev, resolutely rejected classical plow cultivation.Then, in Kazakhstan and Altai, under the leadership of academician VASKhNIL AI Baraev, a harmonious system of moldboard-free tillage was developed and successfully introduced in several regions of the USSR.

Tillage similar to the systems of Maltsev and Barayev was carried out and recommended by the French peasant Jean and the American agronomist Faulkner. Farmers in the US and Canada have now completely abandoned the use of the plow, and there is clearly a desire for minimal tillage. This reduces the risk of soil erosion and drastically reduces labor costs.

So the plow is already yesterday's farming day? Quite possible...

Similar documents

Human development in the course of evolution. The first tools of labor, the use of fire. Everyday life of Cro-Magnons and their descendants. Agriculture, stone tools of labor and hunting. Invention of the wheel, ceramics, spinning and weaving. Discovery and processing of metals.

abstract, added 02/27/2010

Stages of formation and development of primitive people in modern, variants and features of periodization of the ancient history of mankind. The era of the Paleolithic and its main stages, found tools. The process of transition from an appropriating economy to a producing one.

test, added 01/28/2009

Periodization of ancient history. General scheme of human evolution. Archaeological finds of the Early Paleolithic. The influence of the geographic environment on the life and evolution of mankind in the Mesolithic. Division of labor in the Neolithic era. The fertility cult of the Trypillian culture.

abstract, added 11/13/2009

Historical stages of development of society in terms of the way of obtaining means of subsistence and forms of management. Improvement of tools of labor, technology and human development as the basis for the development of society. Social process, the economy, the sphere of labor and life.

presentation added on 02/12/2012

Remains of Australopithecus skeletons in South and East Africa, Australia. The first tools of labor of primitive man. Pithecanthropus and Sinanthropus. Major trades most ancient people... Lower, Middle and Late Paleolithic. The era of the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Eneolithic.

presentation added on 10/09/2013

Analysis of the primitive forms of culture, art and religion of the ancient human society. Descriptions of the formation and development of language. Tools and occupations of the Bronze Age tribes. Population of the Dniester-Carpathian lands. Roman conquests. Romanization process.

abstract, added 03/09/2013

Primitive communal system as the longest period of human development, its signs, periodization. Chronology primitive society, the development of certain forms of labor and social life. The emergence of tools of labor, the transition to a sedentary form of life.

article added 09/21/2009

The means of subsistence of people in the primitive communal system. Improvement of hunting tools, their use. Javelin and boomerang throwing by Australians. The invention of the bow and arrow. The appearance of a polished stone ax. Differentiation of labor of men and women.

presentation added on 11/30/2012

Subject of the history of the Tajik people. The main periods of the primitive communal system. Material periodization according to the tools of labor of the ancient material culture found by archaeologists. Historical source about the development of tools and changes in people's lives.

report added on 02.19.2012

Development and invariant characteristics of individual civilizational systems and human civilization as a whole. Evolution of the concept of civilization. The cyclical concept of the development of civilizations, the reasons for their decline and death. Anthropological concept of culture.

The primitive communal system, through which all the peoples of the world passed, covers a huge historical period: the countdown of its history began hundreds of thousands of years ago.

The basis of production relations in the primitive communal system was collective, communal ownership of tools and means of production, due to an extremely low level of development of productive forces. The labor of primitive man could not yet create a surplus product, i.e. a surplus of livelihoods in excess of their necessary minimum living standards. Under these conditions, the distribution of products could only be equalizing, which, in turn, did not create objective conditions for inequality of property, exploitation of man by man, the formation of classes and the formation of the state. Slow development of the productive forces was characteristic of primitive society.

Leading a herd, semi-nomadic lifestyle, primitive people ate plants, fruits, roots, small animals, and hunted large animals together. Gathering and hunting were the very first, ancient branches of human economic activity. For the appropriation of even the finished products of nature, members of the primitive herds used primitive tools made of stone. At first, these were rough stone hand choppers, then more specialized stone tools appeared - axes, knives, hammers, side-scrapers, sharp-points. People have learned to use bone as well - for the manufacture of small sharpened tools, mainly bone needles.

One of the first turning points in the development of economic activity of people of the period of the primitive herd was the mastery of fire by means of friction. F. Engels, who studied the material culture of the primitive communal system, emphasized that in its world-historical significance, the action liberating mankind, the production of fire by man was higher than the invention of the steam engine, since it first gave people dominion over a certain force of nature and thereby finally pulled them out of of the animal world.

Remarkable is the fact that the discovery of the method of obtaining and using fire occurred during a severe ice age. About 100 thousand years BC in the northern parts of Europe and Asia, due to a sharp cold snap, a huge ice sheet formed, which significantly complicated the life of primitive people. The onset of glaciers forced man to mobilize his forces as much as possible in the struggle for existence. When the glacier began to gradually retreat to the north (40-50 thousand years BC), noticeable shifts were revealed in all areas of primitive material culture. There was a further improvement of stone (flint) tools, and their set became more diverse. The so-called composite tool appeared, the working part of which was made of stone and bone and mounted on a wooden handle. It was more convenient to use, more productive.

The achievements of primitive people in the manufacture of tools led to the fact that hunting began to come to the fore more and more, pushing back gathering. Hunting objects were such large animals as mammoth, cave bear, bull, reindeer. In places rich in hunting, people created more or less permanent settlements, built dwellings from poles, bones and skins of animals or took refuge in natural caves.

After the end of the ice age, the natural environment became more favorable for human life. The period of the so-called Mesolithic - the Middle Stone Age came (approximately from the 13th to the 4th millennium BC).

In the Mesolithic era, another major event in the life of primitive man took place - a bow and arrows were made. The range of the arrow was much greater than the throw length of a spear or other throwing weapon. Thanks to this, bow and arrows became widespread, and hunting began to be carried out not only for animals, but also for birds, providing people with constant food. Along with hunting, fishing began to develop with the use of harpoons, nets and stockades.

The increasing variety of economic activities and the improvement of tools of labor in primitive society led to the revival of the sex and age division of labor. Young men began predominantly to hunt, old men to make tools, women to gather and run a collective household. At the same time, an objective need arose to strengthen ties between members of primitive society. In connection with the development of the economy, a more stable and solid social organization was needed. This kind of organization became the primitive consanguineous community.

The genus usually included several tens or hundreds of people. Several clans made up the tribe. In tribal communities there was no private property, labor was joint, and the distribution of products was equal. Initially, the dominant position in the tribal primitive community was occupied by a woman (matriarchy), who was the continuer of the clan and played a dominant role in obtaining and producing means of subsistence. The ancestral maternal community existed until the Neolithic era, which became the final stage of the Stone Age.

The most important event in the Neolithic era was the transition from an economy based on the appropriation of natural products to an active influence on nature, to the production of food. It was in this era that such enormous importance of the economy as cattle breeding and agriculture arose.

Primitive cattle breeding appeared on the basis of hunting. Hunters did not always kill caught wild young animals (piglets, kids, etc.), but kept them behind a fence. The domestication of animals began, their breeding under human control.

Primitive agriculture emerged from gathering. The irregular and disorganized collection of wild fruits and edible roots began to be replaced by sowing seeds in the ground. This has greatly increased the amount of food that humans receive. The first agricultural tool used in the primitive economy was a simple bathing stick. Gradually, it was replaced by a hoe - a more advanced and already specialized agricultural tool. Hoe farming was a very laborious occupation and gave low yields, but still better provided the members of the clan with food. Through efforts primitive farmers a wooden sickle with a flint attachment was also created. The first cultivated food plants on earth include barley, wheat, millet, rice, kaoliang, beans, peppers, corn, pumpkin.

The transition from hunting and gathering to cattle breeding and agriculture was first made by the tribes who lived in the valleys of the Tigris, Euphrates, Nile, Ganges, Yantsyjiang rivers, in Western Asia, in the southern part of Central Asia, in Central and South America... Animal husbandry and agriculture in their totality constituted agriculture - the main branch of primitive economy. In the course of the further development of agriculture, some tribes, based on the characteristics of the habitat, began to specialize in cattle breeding, others in agriculture. This is how the first large social division of labor took place - the separation of cattle breeding from agriculture.

5. Agriculture. Perpetual motion machine already existed in prehistoric times

The concept of soil productivity for our urban civilization is something secondary. We have it more associated with the chain of stores and the opener for cans than with the soil itself. And if our thought goes much deeper, to production itself, then in our imagination a person appears at the wheel of a tractor or following a horse team. This representation is very colorful, but it has no close connection with our everyday worries about our daily bread.

Love for the land is inherent in the rural population of the whole world, however, according to my observations, there is no other area on the globe where people would have a more mystical attitude towards the products of the land than in Central America. For the Maya Indians, corn is something extremely sacred. In their opinion, this is the greatest gift that the gods have given to man, and therefore he must be treated with respect and humility. According to Mayan customs, on the eve of uprooting the forest or the beginning of sowing, they strictly observed fasting, abstained from sexual intercourse and made sacrifices to the gods of the earth. Religious holidays were associated with each phase of the agricultural cycle.

J. Eric S. Thomposn.

The origin of farming

Today our good old lady Earth feeds about 5 billion people. And it seems at first glance incomprehensible, why 40 thousand years ago (we are not even talking about more distant times) could not provide food for a thousandth of the modern population? Anyone who has carefully read the previous chapter knows the answer - the reason was primarily in the way of obtaining food. People could only live where there was a sufficient number of animals or plants suitable for food. A small group of people needed a huge area around their temporary camp to ensure its food. After the depletion of these hunting grounds, the group was forced to move to a new location. Due to such constant transitions along difficult hunting trails, Paleolithic mothers could not bear and raise more than one child. Considering the high infant mortality rate, it is not surprising that the population grew extremely slowly during the Paleolithic period. At the end of it, that is, 12 thousand years ago, only about five million hunters and gatherers lived on the whole earth. In the struggle with nature, people had only one goal - to survive. But this does not mean that people only passively adapted to natural conditions, not at all. They constantly improved their hunting and gathering techniques. And not far was the time when they ceased to constantly depend on the vagaries of nature.

This time came when the first ear grew out of the deliberately sown grain and the first animal was tamed. This moment was the beginning of such epoch-making changes that scientists did not hesitate to call a revolution (with a clarification - agricultural or neolithic). This is the term we usually define as fast, drastic change. But in ancient times, "speed" had its own terms, which were counted in centuries and millennia. Its origins were those human ancestors who accumulated knowledge about plants. Late Paleolithic and Mesolithic gatherers through experience. Inherited from all previous generations. Perfectly navigated the world of plants. They knew how to distinguish between edible, medicinal and poisonous plants, highly appreciated the nutritional properties of starchy grains of wild cereals. Then they saw that their favorite plants grew better if the others growing nearby were weeded out. After many deliberately and unconsciously conducted experiments, they found that the areas of germination of cereals can be expanded if the grain is sown into the soil at the appropriate time. This also led to the idea of \u200b\u200btransferring seeds to those places where they had not grown in the wild before. Only those gatherers who lived in places where wild-growing cereals were found could have come to such a radical discovery.

In the Middle East (Anatolia, Iran, Israel, part of Iraq, Syria), agriculture appeared simultaneously with cattle breeding in the ninth-seventh millennia BC. e., in Central America from the middle of the eighth millennium BC. e., and in the Far East a little later. People stopped looking, that is, collecting food, they began to produce it themselves. This, in turn, caused a kind of chain reaction. The need to store supplies and prepare food required the creation of containers and utensils - pottery was created; perfect stone axes are needed to clear the forest; the cultivation of flax and other industrial plants, as well as the raising of sheep, led to the emergence of spinning and weaving. But above all, settlements with permanent dwellings grew up near the field. A person's dwelling became better, more comfortable, here women could raise a larger number of children. Therefore, the population of agricultural regions doubled in each generation. In the fifth millennium BC. e. the world's population has reached 20 million. As a result, over time the problem of overpopulation arose in the original centers of agriculture. Some of the inhabitants were forced to leave in search of new lands suitable for cultivation. After some time, the process was repeated in a new place, and gradually the farmers colonized territories that were previously empty and rarely inhabited by a few groups of gatherers and hunters. In this way, agriculture spread from the Middle East to the Balkans, from here to the Danube Lowland and somewhere in the fifth millennium BC. e. farmers appeared on the territory of modern Czechoslovakia.

At that time, Central Europe was almost everywhere, with the exception of small islets of the steppe and forest-steppe, was covered with forests. The colonists occupied the fertile edges, and then, with the help of stone axes and fire, began to recapture the first pieces of fields from the forests. With the help of stone axes, hoes made of wood and horn, digging sticks, they were able to cultivate such an area, the harvest from which provided them with modest food. Ash of burnt trees and bushes contributed to the preservation of soil fertility for about 15 years. Then the land was depleted. Farmers assumed that it was ash (along with magic spells) that gave miraculous power to the soil. Therefore, they moved their settlement to another place, burned and uprooted a new section of the forest. They returned to their old place only 30–40 years later, when a forest again grew there. In Bilany (Czechoslovakia), archaeologists have established that ancient farmers returned to their original place more than twenty times. Their life was like some kind of vicious circle. Primitive tools and too laborious techniques for cultivating the land and harvesting the crops forced them to change places of settlement. Only during the Eneolithic period did the situation of the farmer improve. A rally appeared with oxen harnessed to it. A plowman, with the help of a pair of oxen, could work a much larger area of \u200b\u200bthe field easier and faster than his ancestors.

You may be surprised that the agricultural cycle has remained almost unchanged from ancient times to the present day. Yes this is true. The modern farmer, just like the ancient one, works and prepares the soil for sowing, sows seeds and looks after cultivated plants during their growth. It is necessary to harvest the crop and carefully preserve part of it for future sowing. At the same time, you need to take care of your pets. The practice and the means by which the agricultural cycle is carried out have changed. There is a huge difference between the work of the modern farmer and the farmer of the distant past. Therefore, we are forced to reconstruct the ancient methods of cultivating the land by carefully studying the most insignificant archaeological finds and researching that primitive agriculture that has survived in some remote places on the globe to the present day. Based on these data, it was planned to conduct experiments, the participants of which, in terms of their knowledge, differed little from the first farmers.

Field preparation

In wooded areas, a section of the field had to be recaptured from the forest. In ch. 14 we will take a closer look at ways to cut and clear a forest. The experimenter, using a stone Neolithic ax, cleared a forest with an area of \u200b\u200b0.2 hectares in a week, a copper ax accelerated the same work twice, and a steel one - four times. In the 18th century in Canada, a lumberjack with a steel ax cut down a 0.4 hectare forest in a week.

If the clearing of the site was planned in advance, that is, the farmers did not prepare the site immediately, but for several years, then for a start, ring notches were made on the tree. As a result, the tree dried up and it was easier to then topple it. Thick trees with hardwood at the ring notch were burned.

A special method of felling was used on the slopes. First, they made notches in the trees in certain rows. Then the top row of trees was cut down. Falling down the slope, they, as it were, along a chain, dumped the lower cut ones.

In this way, forests were cleared in some areas until recently. Russian peasants of the 18th – 19th centuries, while developing new lands in the east, first carefully chose a site, taking into account the species of trees, as well as the possibilities of hunting in the vicinity. Plots with thickets of alder were preferred, since it, when burned, gave more ash than other tree species. In addition, the type of trees told them about the nature of the soil and its suitability for cultivation. The trees were first given ring notches or bark removed to dry. After 5-15 years, the trees fell on their own. But in some areas, trees were cut down immediately. This was done in June, when the first field work was completed and a hot, dry summer set in. The felled trees were evenly spaced throughout the site and left for 1-3 years to dry. Then they were burned. They carefully watched that the fire was slow and burned through the ground to a depth of 5 cm. Thus, they simultaneously destroyed the roots of plants and weeds, and a layer of ash was formed even over the entire area of \u200b\u200bthe site.

This method of slash-and-burn farming was exactly matched by an experiment conducted in Denmark. The purpose of the experiment was to simulate Neolithic agriculture. Danish experimenters first of all cut down a section of oak forest with an area of \u200b\u200b2000 square meters with copies of Neolithic axes. m.Dry trees and bushes were evenly placed throughout the entire plot, and then they set fire to a strip 10 m long. They made sure that the soil did not heat up, did not bake, but only so that the plants and remnants of bushes and roots burned and thereby improved soil fertility thanks to ash and liberated mineral salts.

In search of new plots for cultivation, farmers also came across wetlands that had to be drained first. Such ancient works were imitated by an expedition from Lithuania. Drainage of the site could only be ensured by digging a drainage channel. At first, two experimenters tried to dig it with a stake sharpened at an angle of 15–20 degrees, but this stake turned out to be unsuitable for work. The experimenters improved their tool by sharpening the lower end of the stake in the shape of a chisel with a tip width of about 5 cm. With this stake, they cut through the sod layer with several blows and carried the sod to the edge of the canal in pieces. The layer of humus lying under the sod was first dug with the same pointed stake, and then thrown out with wooden shovels, and the same was done with the clay lying below. The entire workflow, during which more than 12 cubic meters were moved. m. of land, took 10 eight-hour working days. The length of the canal was over 20 m, the width in the main part was 180 cm, and at the end it was 100 cm. The depth of the canal varied from 20 to 75 cm. From nine-tenths of an area of \u200b\u200b300 sq. m came off 100 cubic meters. m. of water. The site was drained.

Digging and plowing

The section of the field, cleared by the ancient farmers using the slash-and-burn method, was enough to easily loosen or dig up with simple hand tools before sowing. Along with wooden and horn digging sticks, which were still used by collectors, various types of hoes appeared, which became universal agricultural implements, they not only dug and loosened the soil, but spud tuberous and shrub plants. They deepened drainage trenches, canals, etc. Ancient farmers made hoes from split boulders of various rocks, large pieces of flint and horn, which were attached to handles made of oak, ash and other hard woods. The working part of the hoe was not finished very carefully, only the point was sharpened. And there was no need to do this, because both smooth and rough hoes entered the ground equally. In addition, during work, she herself was polished with solid particles in the soil.

Lithuanian experimenters have tested a whole series of replicas of these hoes with a one and a half meter handle. Their weight was from 700 g to 2 kg. With almost all of them, they achieved the same result. One worker dug 15–20 cm deep into a 15 sq. M. Field. m. (With an iron hoe weighing 2.5 kg, work progressed three times faster. The benefits of working with it were even greater when working on hard soil or soil with a layer of turf.) A flint hoe with an uneven surface after an hour of work became polished to a shine, kinks and traces in the form of grooves appeared on the tip. In accordance with widespread opinion, the experimenters were convinced that the plant fibers or tendons of animals with which the working part of the hoe was tied to the handle would quickly fray. To their surprise, this opinion was not confirmed in practice, since the mount was quickly covered with clay, which hardened and turned into a kind of protective crust.

Then they decided to prepare for sowing a site overgrown with tall grass. In six hours, two experimenters removed the sod layer with the help of oak stakes, while at the same time slightly loosened the soil under the sod. After two or three blows, the stake went to a depth of 20 cm. The sod was removed with rectangles weighing up to 15 kg. The cleaned area was loosened in 4 hours, all the work on preparing the site for sowing was done in 10 hours. With the help of a hoe made of iron or a horn, the same work was done in 3 hours and 20 minutes.

In some parts of the world (India, Mesopotamia, the Arabian Peninsula, etc.), even today, loosening sticks and hooks are used to carry out furrows and loosening the soil, which people pull on ropes. Perhaps this method was used in antiquity, but we do not have archaeological data on this. Lithuanian experimenters have made sure from their own experience that this method is extremely difficult and exhausting. Two men, resting their arms and chest on the pole, pulled a burrowing stick or hook from an oak branch, which the third man pressed into the ground. With this tool, they could only cultivate loosened soil or very soft soil without sod and stones, the resistance of which did not exceed 120 kg.

The facilitation and acceleration of this work was brought only by plowing implements with harnessed animals. The farmers of Mesopotamia used them already at the end of the fourth millennium BC. e. With this method of cultivation, the soil was loosened better, which increased its fertility. In Central Europe, plowing tools appeared only among farmers of the Late Eneolithic, as evidenced by a variety of data, albeit indirect ones (furrows and clay figurines of a team of bulls). The oldest weapons plowing in the form of a wooden hook with an inserted shaft has been preserved since the early Bronze Age and probably did not differ much from the unknown plowing tool of the Eneolithic era. During the laten period (the culture of the Iron Age in Europe), a plowing implement with an iron symmetrical head appeared. The Romans improved it and created a type of asymmetric headboard, which partially turned over (rolled off) the ground. Later our ancestors, the Slavs, also used this kind of ralo.

An experiment with a ral of this type was carried out by the participants of the Lithuanian experimental expedition, which we spoke about above (experiment with digging sticks, stakes and hoes). For plowing, they used two replicas of oak ral, made from archaeological finds in Valle (Germany) and Dostrup (Denmark). In a simpler type from the Vallee of the Bronze Age (1500 BC. The girder and the ralnik formed a single whole. The insert was only a vertical guide stake with a transverse handle. The Ralo was made in a lightweight version weighing 6 kg. The design of the second rally (500 BC) It consisted of five parts, the length of the ridge was over one and a half meters (slightly shorter than the original, since it was supposed to use a horse team, not bulls), and the height of the ral with the inserted transverse handle was 120 cm The length of the side head, fixed with wedges, was 30 cm, and the total weight of the ral was 8.5 kg.

Ralom-type Vallee plowed a field with an area of \u200b\u200b1430 sq. m in 170 minutes, which exceeded the productivity of manual labor by 40-50 times. Cross-plowing of the same area, which improved the quality of its cultivation, took 155 minutes.

Another ral (Dostrup in Denmark) plowed a field with clay soil., Strongly hardened due to the twelve-day heat. A horse was harnessed to the horse, which was led by the bridle. The plowman followed the rally and pressed the ralnik into the ground. Ralnik went deep into the soil on a tuber of 30–35 cm and rolled it on both sides. Field of 250 sq. m plowed in 40 minutes. One furrow 25 m long was plowed in 30-60 seconds. The performance of the wheel compared to hand implements was clear. The same area was cultivated with a loosening stick or hoe for 50 hours. (With the help of the rally, which formed furrows with a depth of 15–20 cm, moreover, the furrows were wider than those plowed by a Valle-type rally, an area of \u200b\u200b1430 square meters was plowed with longitudinal furrows in 400 minutes.)

The ral's effectiveness dropped when it was used on a grassy or uneven field. With a dense interlacing of roots, when the resistance reached 40 kg / cm, it became impossible to work with a Dostrup-type rally. The use of a Valle-type ral on a grassy area was somewhat more effective, since its working part is narrower and sharper, it more easily broke the grass roots, forming a narrow furrow.

Danish archaeologists have found the largest number of different types of plowing tools. This is due to the fact that in the swamps, which are numerous in this country, fossil objects have been preserved. Archaeologists have carried out numerous experiments with copies of ancient agricultural tools. They made one of the replicas of the type of oak plowing tool from Hendrikmose, dated 300 BC. e. It consisted of an onion-shaped oak ralnik inserted into the hole in the lower part of the ridge. A handle was inserted into the drilled hole in the upper part of the seal. A wooden head was attached to the tender pointed part of the tape. With the help of a wedge in the groove of the bead, the handpiece could be moved, changed its angle of inclination and secured. A groove was made in the upper part of the beam to secure the yoke.

For plowing, a pair of trained oxen was needed, which, in terms of their physical characteristics, would be close to the type of the ancients. Two castrated Jersey bulls came up for this. For six weeks they were prepared for plowing, forcing them to drag the felled trees. They were taught to walk in pairs at a slow, even pace. But the oxen refused to walk in a straight line along the furrow and at the end of it turn back. Therefore, the experimenters gave the plowman two assistants who drove the oxen throughout the plowing period.

During plowing, the experimenters studied the effectiveness of the rallying on various types of soil, the angle of inclination of the headstock, the track left by it, the strength of the team. They immediately saw that the shaft, not secured by a wedge, went back until it hit the bend of the pipe. So it was possible to plow only loose soil, without turf. The best plowing option was created when the head was fixed with a wedge and it protruded by 10 cm. In addition, the head was installed at an angle of 35–38 degrees in relation to the bottom of the furrow. In this case, it was possible to plow and virgin soil, which has a solid sod.

The yoke was worn either on the horns of the oxen, or on their neck. True, the angle of the ridge of most Danish rallies indicates rather that the yoke was put on the horns. In this way the best draft line was achieved. The benefit of the second method is that the ox can move its head from side to side. With a load of 100 kg, the oxen moved slowly forward. As soon as the head penetrated deeper into the soil and the load increased to 150 kg, their movement slowed down. And when the sled penetrated even deeper or bumped into a dense weave of turf and a load of 200 kg arose, the movement of the team almost stopped. When the same field was plowed in order to loosen the already plowed soil, the load reached 100 kg, which did not create any difficulties for the animals.