It is known that for many centuries until the end of the 19th century in the forest zone of Russia, the plow remained the most important and universal tool for tillage. It was the most original Eastern European agricultural implement, significantly different from the rallying and plowing. But where, when and in what ethnic milieu did the Sokha appear?

Archaeological materials about plows are rather scarce. These are mainly iron tips (plowshares), as well as iron particles of plow policemen and the only (now lost) wooden part of an ancient plow - a rassokh found before the revolution during excavations in Staraya Ladoga. The oldest discovered plowshares also originate from Staraya Ladoga and date back to the end of the 1st millennium AD. The coulters found near Novgorod date back to the same time. At the turn of the 1st - 2nd millennium AD, there is a gradual expansion of the area of \u200b\u200bdistribution of the plow: in the X-XI centuries, plowshares originating from the Pskov of the Upper Volga region ( Yaroslavskaya oblast) XI-XII centuries - openers from the Vladimir region, regions of Belarus and Latvia. By the end of the XII - the beginning of the XIII century, plows spread in the Volga Bulgaria. So the plow appears at the end of the 1st millennium AD. e. in the northwest of the European part of the former USSR in a small area conditionally limited to Staraya Ladoga in the north and Novgorod in the south.

But I wonder why the plow was actually born in this area - in the forest zone in which agriculture developed slowly and difficult? The answer lies in the functional properties of the plow, its high adaptation to work just in the forest zone. The Russian plow possessed lightness and high maneuverability, which the best way corresponded to the conditions of plowing areas recently selected from the forest, where there were also large tree roots and stumps. On moist clay soils typical of the forest zone, the light plow did not stick much in the furrow. Also, on stony areas, which are also characteristic of the zone of its birth, the plow was very easy because the two cutting narrow "teeth" of the opener experienced significantly less resistance of the formation compared to one wide one, like in other plowing implements.

For forest soils, an important advantage of the Russian plow was the fact that the openers did not cut the plow layer so much and then turn it over, but loosened it and mixed it, which had a better effect on fertility. Moreover, between the coulters, a narrow strip of land remained untouched, which prevented water and wind erosion.

Probably, the distribution of the plow began at the turn of the 1st and 2nd millennium AD and went from the north in the western, eastern and southern directions. The distribution area of \u200b\u200bthe Russian plow is clearly associated with areas of mixed and coniferous forests, as well as with their specific soils, and the directions of the expansion of the areola coincide with the direction of movement of Slavic colonization, which just went from north to west, south and east. This makes it possible to consider the plow as a component of the East Slavic agricultural culture, which arose in the characteristic conditions of northern forest arable land. Sokhu was borrowed from the Eastern Slavs by many peoples of Eastern Europe.

8 The successive development of the form of Old Russian plowshares from archaeological materials and "ethnographic" plows, based on the peculiarities of the shape, was well traced by A. V. Chernetsov (A. V. Chernetsov, 1972c, fig. 4: 1976, fig. 1).

9 The dating of a large asymmetrical share from Veseli na Moravia in Czechoslovakia to an earlier time (Sack F., 19636, Fig. 5, 2) requires careful verification.

10 It has already been noted that the steam farming system in the form of a two-field was known in places in ancient times. Western European written sources testify

0 its presence outside the Roman Empire at the beginning of the 7th century. The first mentions of the threefields for the same areas are found in the VIII century, and for the IX-X centuries. become numerous. However, the two-field along with the three-field is noted here even in the XIII century. and later (Agriculture..., 1936, p. 9, 11, 13, 47, 49, 192). For Eastern Europe, except for the Northern Black Sea region, the nature of the sources does not allow us to accurately determine the time of transition to the steam system. The studies of A.D. Gorsky (Gorsky A.D., 1959, 1960) and G.E. Kochin (Kochin G.E., 1965, pp. 231-248, 431) convincingly proved that by the end of the 15th century. in North-Eastern and North-Western Russia, the final victory of the steam system in the form of a three-field system with the systematic use of manure fertilization takes place. A little later this happened in the Baltic States (Doroshenko V.V., 1959; Ligi //., 1963, pp. 82-89; Yurginis Yu.M., 1966), and also, probably, in the Middle Volga region. But if by the end of the XV century. the three-field, that is, a sufficiently developed form of the steam system, finally won out even in the forest zone, then the beginning of its formation should be assumed at a much earlier time. We have already noted that the presence of individual elements of the steam system in the forest-steppe cannot be denied even for the middle

1st millennium BC e „and even more so for the 1st millennium AD. e. In this regard, it seems quite probable that V.I.Dovzhenko's assumption about a very large, probably leading, role of the steam system in the form of a two-field and, perhaps, a three-field already in Kievan Rus (Dovzhenok V.I., 1961, pp. 119 - 125) , especially in the areas of the forest-steppe and the southern outskirts of the forest zone. On the main territory of the forest zone in the XI-XIII centuries. there is an intensive transformation of the undercut into long-term zero, which began at an earlier time. Such zeros could be processed both according to the transfer system (Rasins A.P. 1959a, 19596), and according to the steam in the form of a two-field, nestropol, and sometimes a three-field (see, for example: G.K. Kochin, 1965, p. 91; Moora X., League X., 1969, p. 5; Krasnov Yu.A., 1973, p. 37; Korobushkina G. Ya., 1979, p. 96-102).

The peculiarities of the plow, which make it possible to distinguish it from other arable implements, and the scope of its application, it is advisable to consider on ethnographic material. Ethnographic data also make it possible, at least presumably, to outline a number of important issues in the early history of this weapon.

Plows, both in the people and in the scientific literature, are called tools that are very different in design, the most characteristic feature of which is the presence of a bifurcated working body, two-toothed (Zelenin D.K., 1907, pp. 20, 21. See also Sreznevsky I.I. ., 1912, t. III, stb. 469; Vasmer M., 1955, p. 703).

The word "plow" in the meaning of a plowing tool is East Slavic and is not found in the languages \u200b\u200bof the southern and western Slavs. This may indicate a relatively late appearance of it - at a time when the common Slavic language no longer existed. It is important to emphasize that among the non-Russian peoples who used plows, along with their local names, 'often identical or close to the names of Rala, there were terms that go back to the word “plow”. So, among the Estonians, plows were called both "ader", and "sahk", "sahkader", "harksahk" (Feoktistova Jl. X, 1980, p. 65), among the Chuvashes - "aka", "akapus" (i.e. arable tool in general) and "sahapus" (Nikol'skiy N.V., 1929, p. 24; Vorobiev N., Ilvova A.N., Romanov I.R., Simonova A.R., 1965, p. 144), among the Germans - and "Stagntta", "Soche" (Leser P., 1931, p. 321). Among the Tatars of the Volga region and the Bashkirs, the names of the plow (respectively "bitch" and "Luk") are borrowed from the Russian language (Khalikov N.A., 1981, p. 61; Yanguzin R. 3., 1968, p. 323). A similar phenomenon is observed in most of the Finno-Ugric peoples (Maninnen /., 1932). These circumstances can serve as an important argument in favor of the fact that the plows fell to the non-Russian peoples of Eastern Europe from the Eastern Slavs.

Among arable implements, called plows, the most representative and widespread group is made up of the so-called Russian or Great Russian plows, in the structure of the body of which peculiar features are especially clearly traced. The name "Russian (Great Russian) plow", firmly established in the literature, is rather arbitrary: plows of the same device were used not only by Russians, but also by Belarusians, Ukrainians, Finno-Ugric, Baltic and Turkic peoples of Eastern Europe. In the XVIII-XIX centuries. the area of \u200b\u200bthe Russian plow stretched from the Baltic in the west to the Urals in the east and from the northern limits of the spread of agriculture in Eastern Europe to the southern borders of the forest-steppe, mostly coinciding with the subzones of coniferous and mixed forests, where podzolic and sod-podzolic soils predominated (Zelenin D., 1907; Novikov Yu. F., 1962, pp. 461-463; Gromov G. G, 1967; Naidich D.V., 1967, map 1). The plow was brought into Siberia by Russian settlers. Cases of the use of plows in the central regions of Ukraine (Gorlenko V.F., Boyko 1.D., Kunitsky O.S., 1971, p. 56) and in the steppe Volga region (Zelenin D., 1907, p. 138, 164- 166).

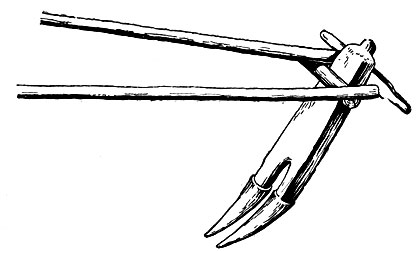

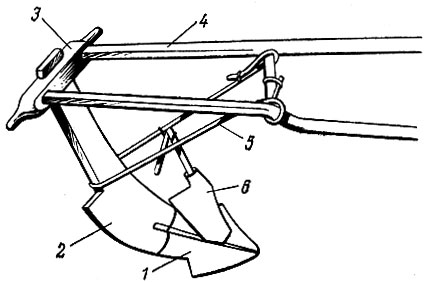

In some areas, the Russian plow was distinguished by the details of the device, but everywhere it retained the general design scheme and specific features of the device. component parts (fig. 3, 82). Its main part was a rassoka - a wide block or plank bifurcated in the longitudinal plane and, as a rule, bifurcating at the lower end, forming the working part of the tool (Fig. 3, 1, a). With a lack of suitable wood for solid crusts, they were sometimes made up of two separate curved beams fastened by transverse crossbeams. Composite scraps are historically younger than whole ones (Zelenin D, 1907, p. 45, 46). The most common name for the working part of the plow - "rassokha" - is associated with the name of the tool itself and emphasizes its bisectedness, other names - "dam", "block", "flesh", "swara", etc. - indicate the density, strength of this part ... Rassokha functionally corresponds to the rallies at the rallies, but differs significantly in design. Its length was determined by the height of the plowman and did not exceed 0.9-1.05 m. The width of the teeth of the rass is always less than the width of the blade of the single-toothed ral.

Russian plows of the 18th-19th centuries, as a rule, were two-toothed. As an exception, there are known, on the one hand, single-toothed, and on the other, multi-toothed tools, which otherwise have all the features of a Russian plow. Data on multi-toothed tools with a coulter body (Fig. 83, 1) are limited, dating back to no earlier than the 19th century. and belong to the Russian population of certain areas of the former. Arkhangelsk, Kostroma and Novgorod provinces (Review agriculture... ... ., 1836, tab. II, no. 2; Cannon - roar I., 1845, p. 52; Novgorod collection. ... ., 1866; Agricultural statistics. ... ., 1903, p. 313; Supinsky A.K., 1949). Also scanty are data on single-toothed plows (Fig. 83, 2, 3), known in some areas of the former. Novgorod (Naidich D.V., 1967, p. 39) and Vyatka (Materials for agricultural statistics....., 1885, p. 93) provinces. Some varieties of improved cocks of the late 19th century were also single-toothed. (Vargin V. Ya., 1897, p. 55, fig. 81; Zelenin D., 1907, p. 161). In the old literature, other tools were sometimes called single-toothed plows - roe deer and "blueprints".

On the teeth ("horns" or "legs") of the ridge, which had a length of up to 40-50 cm, iron socketed tips were put on (Fig. 3, 2), called "openers", "omeshes", "ralniks". According to the samples we measured, their length was from 21.5 to 45 cm. According to the relative width of the sleeve and the working part, they are divided into stakes and feathers. In the stalk openers, which often had a symmetrical blade, the width of the sleeve and the blade is the same; in the feather openers, the blade is wider than the sleeve, asymmetric and looks like an elongated versatile triangle. The coulters were mounted on the “legs” of the rass at a certain angle to each other, so that they made a groove-like furrow. Plows with different types of openers are called stakes and feathers, respectively. The latter in the 19th and early 20th centuries. were the most common in the entire area of \u200b\u200bthe plow. Unlike ral, which in the recent past were often used without iron tips, Russian plows usually worked with these latter. This circumstance, as well as the origin of the name of the plow, can be assessed in favor of its relatively late appearance.

The upper end of the rassok was fastened to a bagel - a horizontal bar located perpendicular to the direction of movement of the gun, the ends of which usually served as handles. In some cases, the crust is hammered into the horn from below, fixing in it with wedges (Fig. 3, I), in others, it is clamped between the horn and a parallel bar - the root, the ends of which are tied (Fig. 84). The first are called horns - lyuha, the second - sidekick. Sokhi-rogalyukhs, apparently, are older than ko - resh ones (Zelenin D., 1907, p. 30). There are no analogies to the rogaly among the parts of rallies and plows.

The Russian plow was intended for one-horse harness, although there were exceptions here. Therefore, the device for harnessing domestic animals took the form of two shafts, functionally corresponding to the beams and plows, but sharply differing in design (Fig. 3, 1c). There are two main ways of harnessing the plow: the most common - without an arc, when the plow had short shafts, in the front ends of which holes were made for pegs, for which the crimps were tied to the tugs of the clamp, and with an arc, to the ends of which the shafts were tied, in this case longer. Sometimes in plows both shafts or only the right one were made crooked. The rear ends of the shafts were usually hammered into the horn, and at a distance of about one and a half arshins from it, they were fastened with a transverse bar, which was called

a ■ - horn, 6 - shafts.

c - list, on the right - normal, on the left - adapted for hitching the drawbar, d - drawbar

Figure: 8G\u003e. Details eoh with ral elements; Ukraine, after V.F.Gorlenko, I.D. Guyko. A. S. Kupntskiy

valen with a list, a support, a spindle, a stepson, etc. (Fig. 3, 1, d). Thus, the Russian plow is characterized by a high, at the level of the plowman's hands, the location of the place of application of traction force. In plows, intended for work on old arable soils, the rear ends of the shafts were sometimes connected not with the horn, but hammered into the upper part of the rasshok (Naidich D.V., 1967, p. 37, Fig. 6, tab. Ill, 1, VIII , 1-3), which achieved a decrease in the place of application of traction force.

On the outskirts of its range, where the Russian plow was adjacent to other arable implements, sometimes a harness of two bulls or

fishing, as well as parokonnaya. Adapting the plow for a pair harness, the shafts were sometimes made converging in front and the bulls were tied to the end of them, as if to a ral ridge (Fig. 84, 1,2). In other cases, the shafts were shorter than usual, and in the middle of the list a beam or drawbar was attached (Fig. 85, 2). In Lithuania, as well as in the Siberian "wheels", the beetle was sometimes hammered into the horn or into a crust slightly below the horn. Sokhi - "kole - dry", which had a wheeled front end, are a late modification of the Russian plow, which appeared, apparently, only in the 19th century. (Zelenin D., 1907, p. 60, 61). Thus, when paired harnessing with a bead, the plows still retained either shafts (in a modified form), or a horn, or both. This allows us to assume that the plows for double harness are historically later than single plows with shafts.

The working part of the Russian plow was connected to the crimps with a flexible connection - rope, bast or twig stocks, which ran crosswise from the bottom of the rass to the middle of the shafts and the list between them (Fig. 3, 1, e). With the help of the rootstocks, the tool was given a certain rigidity, and the angle at which the working part entered the soil was also established. This, along with the weekly Monday, determined the plowing depth. Thus, the rootstocks played the same role as the stand on rallies and plows, but this function received a different constructive solution from the plow. Only in late XIX in. soft rootstocks were sometimes replaced by a wooden rod ("chill") or an iron rod with screws at the ends.

Thus, the Russian plow in its typical and most common form differs from ral and plows, as well as other varieties of plows, in a set of features characterizing the device and method of articulation of the main parts, which includes:

a) manufacturing of all the main parts of the tool from individual parts;

b) connection of the working part and the device for harnessing the animals with the help of a horizontal bar located perpendicular to the direction of movement of the tool;

c) using the ends of this bar as handles;

d) high (usually at the level of the plowman's hands) location of the place of application of traction force;

e) bifurcation of the working part, two-toothed, although there are rare single-tooth and multi-toothed tools with other signs of a plow;

f) use of rope, bast or rod ties between the working part and the device for harnessing animals to stiffen the tool and regulate the plowing depth;

g) one-horse harness, in connection with which the device for harnessing pets takes the form of two shafts.

These features, taken together, form a characteristic plow body, which is not found in other arable implements. Its constituent parts can only functionally be brought together with the most important details of these latter; the constructive solution of each of them and the weapon as a whole is significantly different.

Having, in principle, the same body structure, the Russian plows differed in functional characteristics, which was associated with the presence or absence, as well as the way of installing another part - the police.

Functionally, the simplest type were plows without a policeman with an almost vertical installation of the rake, short and straight stitched openers. Such plows (Fig. 82) plowed very shallowly, only "scribbled", "grabbed" the ground from above. By the nature of the work, they are close to rails without moldboard devices with an inclined working part and a high location of the place of application of tractive force. Plow plows without police include the so-called "herringbone" and part of the "fallow" or "sweeping" plows, used on the lands recently freed from the forest (Preobrazhensky A., 1858, p. 79; Zelenin D., 1907, p. 21-23; Tretyakov P. Ya., 1932, p. 32; Gromov G.G., 1958, p. 145; Feoktistova L. X., 1980, p. 122, 123), as well as "Cherkusha" (" Cherkukha "), which was used in combination with other tools for secondary plowing, plowing seeds, hilling and plowing potatoes, etc. (Naidich DV, 1967, p. 37).

More complex were the plowshares, which had a transfer police, or transfer ones (Fig. 3, 1). DK Zelenin describes the Russian police officer as follows: “For the most part, the police have the appearance of a shoulder blade, but of various shapes: sometimes it is narrowed downward, sometimes the middle is narrowed, etc. Almost always it is somewhat humped, that is, it looks like a chute; it is mainly for convenience to put the police on the ralnik. The police blade is made of iron, and the handle is wooden; for attachment to the handle, the blade has a tube (pipe) ”(Zelenin D., 1907, p. 39). Known policemen in the form of a straight wooden or iron stick (Dashkov V., 1842, p. 77). Perhaps such a form of them preceded the one described above (Kochin G.E., 1965, p. 132, 133). In plows with rootstocks, a policeman was fixed with a handle in these latter, in the presence of a chill, she was tied to it. It was fixed in such a way that it could be transferred from one opener to another.

The functional role of the police (Fig. 3, 1, g, 3) is twofold. On the one hand, it crushes, loosens the soil layer lifted by the coulters, carries it along with it, which turns out to be similar to additional rallers and double dumpers. A policeman in the form of a simple stick plays the role of only loosening the layer of earth. On the other hand, the transfer police to a certain extent rolls the raised and loosened soil to one side or the other. In this way, it is again close to additional plows or a plow blade, but due to its small size and installation method, it is far from identical to the latter. In terms of functional qualities, plowshares with a checkered police should be considered as transitional from moldless tools to plow-type tools, and they are closer to the first than to the second.

Some of the reversible plowshares had an almost vertical installation of the rasshok, like in the case of the plow plows, while in others the plowshares entered the soil almost horizontally. They had both feather and stakes openers. The latter were more often used with plows with a rass close to vertical installation. There were practically no differences in the structure of the case of the transfer and useless dryers.

The next variety of Russian plows in terms of their functional features were plows with a stationary police or plows - one-sided, always equipped with feather openers (Fig. 86). The simplest of them differed from the reversible ones only in that one

Sokha. Harrow. How was bread sown a thousand years ago? In ancient times, more and more not fields, but forests covered the land. First it was necessary to reclaim land from the forest. Usually they chose the right piece of land and burned the forest on it, the ash served as a good fertilizer, then the field was sown with various cereals. The owner of such a plot was called the firemen, and the inhabitants who ate from this land were called firefighters. The peasant plowed the land with a plow two or three times, because it did not loosen the soil well. After plowing, the field was harrowed.

Picture 10 from the presentation "Life of Ancient Russia" to history lessons on the topic "Culture of Ancient Rus"Dimensions: 960 x 720 pixels, format: jpg. To download a picture for a history lesson for free, right-click on the image and click "Save Image As ...". To show pictures in the lesson, you can also download the presentation "Life of Ancient Russia.ppt" for free with all the pictures in a zip-archive. The archive size is 885 KB.

Download presentationCulture of Ancient Rus

"Old Russian culture" - Clay tablet. He wrote. Temple of St. Sophia in Novgorod. Saint sophia. HOLY SOPHIA - Divine Wisdom. Onfim is a Novgorod boy who studied 800 years ago. Old Russian alphabet. Peasant house. Birch. Old Russian culture. How schoolchildren were taught in ancient Russia. Dmitrievsky cathedral in vladimir.

"Yaroslav the Wise" - Yaroslav on the money. MOU "Spasskaya main comprehensive school". Under him the Russian Truth was compiled. Yaroslav the Wise. Sons of Yaroslav the Wise. Established dynastic ties with many European countries. Anastasia became the wife of King Andras I of Hungary, the son of Ladislav the Bald. Daughters of Yaroslav the Wise.

"Holy Russia" - Historical foundations of Orthodox culture. Questions and tasks: And the fields bloom, And the forests rustle, And heaps of gold lie in the ground. And a lot of people have returned home. Red Square. Text with a miniature from the Radziwill Chronicle. Widely you, Russia, Along the face of the earth In regal beauty Unfolded. "The Tale of Bygone Years" by Nestor the Chronicler.

"Culture of Kazakhstan" - Prepared by the teacher of history ShG №10 Imanbalinova E.Sh. The results are aimed at realizing personality-oriented, active approaches; mastering by students of intellectual and practical activities; mastering the knowledge and skills required in everyday life, allowing you to navigate in the world around you.

"Culture of Ancient Rus" - Found in Novgorod in 1951. Grain. And in that one we beat you with a forehead. " Cyrillic. Miniature. Drawing a pattern on a metal surface with a thin gold (silver) wire. Constantine and Elena. Remains of the foundation. Read pages 57-59 of the textbook. 4. Literature. Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod. Culture of Ancient Russia.

"Russia in the 11-13th century" - Princely mansions in Chernigov. In large cities, their chronicles were kept. Torzhok. 16th century engraving. Lesson assignment. Chronicle page. On the walls, on the birch bark, scientists find many inscriptions. Lesson plan. Many goods were sold. Europeans called Russia "Gradariki" - a country of cities. As a rule, the Golden Gate was built at the entrance.

There are 39 presentations in total

The Russian plow occupies a special place in the history of the plow - a specific tool for cultivating the soil of the forest belt. Unpretentious, cut down from a piece of wood with an ax and a chisel, this tool was for a long time the most widespread arable tool in Russia, right up to the October Revolution.

Sokha appeared in ancient times among the Eastern Slavs, whose main occupation was agriculture, the main food is bread. They called him zhito, which in Old Slavic means to live. Under the pressure of the steppe nomads, the Slavs were forced to populate the vast forest spaces between the Volga and Vistula; it was necessary to cut down and burn forests for arable land.

The area of \u200b\u200bthe scorched forest was called lyad, the shrub was called the dry-cut, and the sod was called the egg-bed. The common name for such fields is fires or fires. The farming system that has spread here is called slash-and-burn. The peasants reclaimed from the forest in this way sowed rye, barley, millet and vegetables.

It was important to choose the right site for stubbing. Life experience told smerds that the land in a deciduous forest is better than in a coniferous one. Therefore, the sites were developed as separate islands scattered throughout the forest. After several harvests, the land was depleted and harvests fell. Then a new site was developed, and the old one was abandoned for many years.

In the northern regions of our country, this system was still used in the recent past. Mikhail Prishvin, after visiting Karelia in 1906 in his essay "In the Land of Unafraid Birds", wrote: "In a dense forest on a hill, opposite a forest lake of a white lambina, you can see a yellow circle of rye, surrounded by a frequent oblique hedge. There are forest walls around this island, and a little further away, there are also very swampy impassable places.This cultural island was made by Grigory Andrianov ...

Back in the fall, two years ago, the old man noticed this place when he was in the forest. He carefully examined the forest - whether it was thin or very thick! very thin does not give bread, thick is difficult to whip ...

In the spring, when the snow melted and the leaf on the birch became a penny, that is, at the end of May or at the beginning of June, he again took the ax and went to "chop the bitches," that is, to cut the forest. He chopped a day, another, a third ... Finally, the work is over. The felled wood must dry.

The next year, at the same time, having chosen a not very windy clear day, the old man came to burn the dried, caked mass. He put a pole under the edge and set it on fire from the leeward side. Among the smoke obscuring his eyes, sparks and tongues of flame, he deftly ran from place to place, adjusted the fire until all the trees were burnt out. In the forest on a hillock, opposite the white lambina, the yellow island turned black - it fell. The wind can blow precious black ash from the mound, and all work will be wasted. That is why it is necessary to immediately start a new job. If there are few stones, then you can shout directly with a special fallow plow with straight openers without sticking. If there are a lot of them, the earth needs to be mowed, cut with a manual oblique hook, an old cooper. When this hard work is over, the arable land is ready, and next spring you can sow barley or turnip. This is the story of this small cultural island ... ".

The people glorified the courageous heroes, famous for their military and labor exploits, in epics:

"Ilya went to his parent, to the priest, To that work on the peasant, I must clear it from the oak-well, He cut down everything."

But, even having the heroic strength of Ilya Muromets, it is impossible to cut down the forest for arable land without an ax. Therefore, arable farming in forest areas arose at the beginning of the 1st millennium AD, when the Slavs mastered the production of iron. According to F. Engels, only thanks to the use of iron "it became possible on a large scale to agriculture, field cultivation, and at the same time an increase in vital supplies practically unlimited for the then conditions; then uprooting the forest and clearing it for arable land and meadow, which, again, in large sizes could not be produced without an iron ax and an iron shovel. "

The peculiarity of land development and their use influenced the nature of agriculture and the design of the tillage tools of the Slavs. Obviously, they learned from the Scythian farmers about a loosening tillage tool - a ral and used it to cultivate cultivated soft soils. However, such a tool turned out to be completely unsuitable for processing forest clearing of slash farming. The horizontally placed plowshare clinging to the roots remaining in the soil and breaking off.

Therefore, even before the use of iron, the simplest wooden tool, irreplaceable in slash farming, is a knotted harrow.

A bitch was made right there in the forest from spruce. They chopped off the top, chopped off small branches and left only large ones, chopped off at a distance of 50 - 70 cm from the trunk. The knot was attached to the horse with a rope hooked to the top of the trunk. During the movement, the knotted whale made turns around its axis. Straight teeth - branches easily jumped over the remnants of roots and loosened the soil well. Sukovatka was also used for planting seeds sown on the surface of the field.

Subsequently, the Slavs began to make an artificial knotted plow - a multi-tooth plow. Such tools were used by the peasants of the northern regions even at the end of the last century. They were called pumps. The opener teeth were attached to a special crossbar vertically or with a slight inclination to the soil surface.

This design of the plow was suitable for processing areas cleared from the forest. They were lightweight and highly maneuverable. When it met roots or stones, the plow came out of the ground, rolling over the obstacle and again quickly deepening. At the same time, she loosened the soil well enough.

The choice of the number of plow teeth was determined by the horse's strength. Therefore, two-toothed and three-toothed plows were more often used. In terms of traction, they were quite within the power of a small and weak old Russian horse.

Further improvement of the plow took place in close relationship with the development of the slash farming system. Careful clearing of the field, uprooting large and small stumps and their roots created conditions for cultivating the soil with multi-toothed plows with small iron coulters, and later with a two-toothed forest plow or heron, although the coulters were still installed vertically to the soil and therefore unloaded and furrowed the ground. Finally, a late type of common plow was created that has survived to our times.

In the old days, a plow was called a "fork," any branch, twig or trunk that ends at one of its ends in a split: two horns or teeth. This broad meaning of the word "sokha" is the main and most ancient one. This is confirmed, for example, by the application of the word "plow" to the expression "moose deer". The use of this word in the meaning of "arable implement" is later and more specific.

Initially, the Russian people called this agricultural tool, in which the working body had a forked end. Two ralniks were put on the ends. In Russian folklore, one can often find proverbs and folk riddles confirming the two-toothed plow: "The brothers Danila made their way to the clay"; "Baba Yaga with a pitchfork, feeds the whole world, she herself is hungry."

The frame (body) of the plow is a triangle in shape. One side of the triangle is formed by the plow stand, which forms its basis. It was called Rassokha. The rest of the coulter parts were attached to the rass. The second (upper horizontal) side of the triangle is formed by plow shafts. They were called squeezes. The third side, connecting the bottom of the ridge with the shafts, was formed by the rootstocks.

Rassokha also had other local names: dam, block, paw, wobble, etc. A block is a thick stick slightly curved and forked at the bottom. It was cut down, as a rule, from the bottom of a birch, aspen or oak tree. Sometimes a tree with roots was chosen.

Rassokha was processed and fixed so that the lower forked end was slightly bent forward. Iron tips - ralniks - were put on the horns of the crackers, so that they were facing forward rather than downward. The upper end of the plow was connected to the plow squeezes using a thin rod - horn. The mount was not rigid. Therefore, the rassokha had some free play relative to the horn. Moving the upper end of the ridge forward and backward, we changed the slope of the plow to the surface of the field - we regulated the plowing depth. Rogal also served as a handle for the plowman. Therefore, the expression "to take up the horn" meant to take up arable land.

The rollers were made in the form of triangular knives with a socket for attachment to the crust horns. The ralniki were planted on the crust not in one plane, but in a groove, so that the soil layer was cut both from below and from the side. This reduced traction and made the horse's work easier. By changing the slope of the plow, it was even possible to roll the layers to the side.

For plowing grubbed and stony fields, narrow and long ralniks were placed on the plow, resembling a chisel or a stake. They were called "stake plow", and plow - "stake plow". On old arable lands, cleared of roots and stones, plows with feathers were used. Such feather plows were the most common. The plowing depth was regulated by pulling or lowering the shafts using a wedge, to which their front ends were attached. Raising the shafts reduced the plowing depth, lowering it increased it.

The plowing depth was also changed with the help of twig or rope rootstocks. When the rootstocks were twisted with a stick inserted between them, the angle between the rootstock and the crimps decreased, and the ralnik was set down. The plowing depth decreased. When the rootstocks were unwound, the plowing depth increased.

The plow was not easy to operate. The plowman needed extraordinary strength, since he had to help the horse. The ideal of such a plowman is Mikula Selyaninovich.

Bylina draws Prince Volga at the moment when he meets a free peasant in the field - the plowman Mikula Selyaninovich, and sings the free peasant labor, its beauty and greatness.

"He drove into the open field of the warrior, And yells in the field of the warrior, prodding, From edge to edge of the groove marks. To the edge he will leave - there is no other to be seen, That root, stones all into the furrow, is knocking down. maple, Silk tugs at the warden. "

Mikula Selyaninovich tells Prince Volga:

"They will pull out a fry from the land, They will shake out the land from the omeshiks, They will pry out the omeshiks from the omeshik, I will have nothing, good fellow, peasant"

And when the vigilantes of Prince Volga Svyatoslavovich try to lift Mikula's bipod, the narrator says: "They twirl the bipod after firing around, they cannot lift the bipod from the ground."

Here "yells" - plows; "ratai, oratayushko" - a plowman; "omeshik" - an iron ploughshare at the plow; "burn" - plow shafts.

It is interesting that the word "to plow" was originally used only when working the soil with a plow, and when working the soil with a plow with a seam turn, the word "yell" was used. The plow in its capabilities was a universal tool of the loosening type. She did not have a device for rolling off and turning the soil layer. But the plow was equally suitable for cultivating forest areas of slash farming and for loosening soft cultivated soils.

Talented Russian craftsmen constantly improved the plow, looking for the best design in relation to their conditions, the level of economic development of their economy and the requirements of practical agronomy. Gradually, the plow began to acquire the features of a plow, it had a transfer police, which served as a dump, and later a knife-cutter.

The installation of the police on the plow has taken a significant leap forward in soil cultivation. With such plows it was already possible to cultivate the soil with a partial rotation of the layer, its good loosening, more successfully to destroy weeds and, which is very important, to plow the manure fertilizer.

The plows with the police served as the basis for the creation of more advanced tools: roe deer, saban, Ukrainian plow and other tools, which in their functions stand close to the plow.

SOKHA - one of the main arable implements of Russian peasants in the northern, eastern, western and central regions of European Russia. The plow was also found in the south, in the steppe regions, participating in the cultivation of the land together with the plow. The plow got its name from a stick with a fork, called a plow.

The device of the plow depended on the soil, the terrain, the farming system, local traditions, the degree of the population's provision. The plowshares differed in the shape and width of the plowshares - the boards on which the plowshares (openers) and shafts were fixed, the way it was connected to the plowshares, the shape, size, the number of plowshares, the presence or absence of a policeman - the dump, the way it was installed on the plowshares and the plowshares.

A characteristic feature of all types of plows was the absence of a runner (sole), as well as a high location of the center of gravity - attachment of traction force, that is, the horse pulled the plow by the shafts attached to the upper part of the tool, and not to the lower one. Such an arrangement of the traction force forced the plow to rip open the ground without going deep into it. She seemed to "scribble", in the words of the peasants, the top layer of the soil, then entering the ground, then jumping out of it, jumping over roots, stumps, stones.

The plow was a versatile tool used for many different jobs. She was raised again on sandy, sandy-stony, gray with sandy loam soils, forest dews, carried out the first plowing on old arable lands. The plow doubled and troil the arable land, plowed seeds, plowed potatoes, etc. In large landowners' farms, all these works were carried out with the help of special tools: a plow, a ral, a plow, a plow, a tiller, a cultivator, a hiller.

The plow went well on forest soils littered with stumps, roots, and boulders. She could plow not only dry, but also very wet soil, since she did not have a runner on which the earth quickly adhered, making it difficult to move. The plow was convenient for a peasant family in that it freely worked on the narrowest and smallest arable lands, had a relatively low weight (about 16 kg), was quite cheap, and was easily repaired right on the field. She also had some drawbacks.

The famous Russian agronomist I.O.Komov wrote in the 18th century: “The plow is not enough because it has too shaky and excessively short handles, which is why it is so depressing to own it that it is difficult to say whether the horse that pulls it or the person who rules , it is more difficult to walk with her ”(Komov 1785, 8). Plowing the land with a plow was quite difficult, especially for an inexperienced plowman. “They plow arable land - don't wave their hands,” says the proverb. The plow, not possessing a runner, could not stand on the ground. When a horse was harnessed to it, the plow went unevenly, in jerks, often tipping to one side or deeply burying the coulters into the ground.

The plowman during work held her by the horn handles and constantly adjusted the course. If the plow was very deep into the soil, the plowman had to lift the plow. If they jumped out of the ground, he had to forcefully press the handles. When the plowman encountered stones on his way, he was forced to either deepen the plow into the ground in order to raise a stone on them, or remove the plow from the furrow in order to jump over the stone. At the end of the furrow, the plowman turned the plow, first taking it out of the ground.

The work of a plowman was extremely difficult when the horse was in harness without an arc. Supporting the plow on his hands, adjusting its course, the plowman took over a third of the total pulling power. The rest fell to the horse. The work of the plowman was somewhat facilitated by the arcuate harness of the horse. The plow then became more stable, fell less to one side, walked smoother in the furrow, so the plowman could not hold it “in his hands”. But for this a healthy, strong, well-fed horse was needed, since it was in this case that the main burden fell on her. Another disadvantage of the plow was shallow plowing (from 2.2 to 5 cm) during the first plowing of the field. However, it was compensated by double or triple plowing, secondary plowing of the land “track in track”, that is, by deepening the already made furrow.

The complexity of the work was overcome by the professional skill of a plowman. It can be said with full confidence that the plow, having a wide agro-technical range, being economically affordable for most of the farmers, was the best option for arable implements, meeting the needs of small peasant farms. Russian peasants highly appreciated their plow - “mother-nurse”, “grandmother Andreyevna”, advised: “Hold on to the plow, to the crooked little leg”.

They said: "Mother bipod has golden horns." A lot of riddles were made about the plow, in which its design was played well: "A cow went on a spree, plowed the whole field with horns", "The fox was barefoot all winter, spring came - went in boots." In some riddles the plow took anthropomorphic features: "Matushka Andreevna stands hunched over, her little legs in the earth, spread her little hands, wants to grab everything." In the epic about Volga and Mikula, an ideal image of a plow is created, which the peasant hero Mikula plows with: A maple bipod at a warrior, Omeshiks on a damask bipod, A silver bipod on a silver bipod, Rogachik at a bipod is red gold.

The plow is an ancient tool. Archaeologists have found the slugs in the cultural layers of the 9th-10th centuries. The first written mention of the plow dates back to the 13th century. This is a birch bark letter from Veliky Novgorod, sent by the owner of the land, probably to his relatives in 1299-1313. In translation, it reads like this: "And if I send the openers, then you give them my blue horses, give them with people, without harnessing them to the plows." The plow as a plowing tool is also mentioned in a paper document written by Dmitry Donskoy around 1380-1382. The earliest depictions of plows are found on miniatures of the 16th century Litsevoy Chronicle Collection. The plows that existed in Ancient Russia were not a complete analogue of the plows of the 19th century.

In the pre-Mongol time, plows without pblits with code ralniks prevailed, while plowshares were smaller and narrower than plowshares of peasant arable implements of the 19th century. Their sizes ranged from 18 to 20 cm in length, from 0.6 to 0.8 cm in width. Only in the 14th century did longer spearheads with a sharpened blade and one cutting side begin to appear, approaching in type to those of the 19th century. According to historians, a two-toothed plow with feather plows and a sliding table appeared at the turn of the 14th-15th centuries. or in the 16th century, i.e. when the development of large tracts of land with characteristic soil and landscape conditions by the Russians began.

Plow double-sided

A soil tillage implement with a high pulling force attachment used for plowing on light soils with a lot of roots as well as on well tilled land. The body of a double-sided plow consisted of a rass, two ralniks, a horn, a shaft, and a policeman. The plow rassokha was a slightly curved board with a fork - horns (legs) - at the end raised up. It was cut from the butt of oak, birch or aspen, trying to use strong roots for the horns. The width of the ridge was usually about 22 cm.

The average length was 1.17 m and, as a rule, corresponded to the height of the plowman. Iron ralniks were put on the plow horns, which consisted of a pipe, into which the ridge horn entered, a feather - the main part of the ralnik - and a sharp nose at its end, 33 cm long. narrow and long, like a stake or chisel. The first ralniks were called first, the second - code. The feathers were wider than the coded ones, about 15 cm, the stakes were no more than 4.5-5 cm wide.

The upper end of the ridge was hammered into the horn - a round or four-sided thick bar about 80 cm long in cross-section, with well-hewn ends. Rassokha was hammered into it loosely, gaining the possibility of some mobility, or, as the peasants said, "slacking." In a number of regions of Russia, the rassoka was not driven into the bagel, but was clamped between the bagel and a thick bar (box, pillow), tied at the ends to each other. Shafts were tightly driven into the horn for harnessing the horse. The length of the shaft was such that the ralniki could not touch the horse's legs and injure them.

The shafts were fastened by a wooden crossbar (spindle, stepson, binder, list, controversial). A stock was attached to it (felt, earthen, mutiki, cross, prick, string) - a thick twisted rope - or vitsa, i.e. intertwined branches of bird cherry, willow, young oak. The stock covered the rootstock from below, where it bifurcated, then its two ends were lifted up and fixed at the junction of the crossbar and the shafts. The stock could be lengthened or shortened using two wooden sticks-rivets, located near the shafts: the rivets twisted or untwisted the rope.

Sometimes rope or twig rootstocks were replaced with a wooden, even iron rod, which was reinforced in the crossbar between the shafts. An integral part the plow was a policeman (gag, floor, blade, suction, shabala) - a rectangular iron spatula with a slight curvature, slightly resembling a groove, with a wooden handle, about 32 cm long. tied to the stock, and with a wooden rod, it passed into a hole hollowed out in it.

The policeman was relocatable, i.e. shifted by a plowman from one man to another at each turn of the plow. The double-sided plow was a perfect tool for its time. All of its details have been carefully thought out and functionally conditioned. It made it possible to regulate the plowing depth, make an even furrow of the required depth and width, lift and turn over the ground cut by the plows. The double-sided plow was the most common among Russian plow. It is generally accepted that she appeared in Russian life at the turn of the XIV-XV centuries. or in the XVI century. as a result of the improvement of the plow without police.

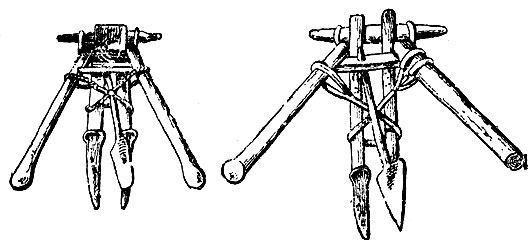

Sokha-one-sided

Tillage tool, type of plow. The one-sided plow, as well as the two-sided plow, is characterized by a high attachment of traction force, the presence of a wooden scissor bifurcated at the bottom, feathers and pblitz. However, the one-sided plow had a more curved shape than the two-sided plow, and a different arrangement of the ralniks. The left plow of such a plow was placed vertically to the surface of the ground, while the other was lying flat. A metal policeman was attached to the left ralnik - an oblong scapula narrowed towards the end. On the right side, a small plank was attached to the masonry - a wing, which helped to roll off the layers of earth.

There were also known other methods of installing video clips and pblits. Both radials were installed almost horizontally to the ground. The left ralnik, called the "little man", had a wide feather with a fleece, i.e. with one of the edges bent at a right angle. The right fist ralnik ("little woman", "little woman", "woman") was flat. Pblitsa lay motionless on the left wing, resting its lower end on the wing. A wooden or iron plate was inserted into the pipe-maker of the right ralnik - a dump.

When plowing, the left opener, which stood on its edge (in the other version of the wing), cut the soil from the side, and the right opener - from the bottom. The land came to the police and was always thrown to one side - the right. The dump on the right side of the crack helped to turn the layer. One-sided plows were more convenient for the plowman than two-sided plows. A plowman could work for "one omesh" without tilting the plow to one side, as he had to do, cutting the seam on a double plow. The most successful was the fly plow.

Owing to two closely spaced, horizontally located grooves, the furrow was obtained much wider than in a plow with a vertically placed groove, in which the width of the groove was equal to the width of one groove. One-sided plowshares were common throughout Russia. Especially plows with fleece. They were one of the main arable tools in the northeastern part of European Russia, in the Urals, Siberia, and were found in the central regions of the European part of the country.

In the second half of the XIX century. at the Ural factories, they began to produce more advanced one-sided plows with a fly. Their crack ended with one thick horn-tooth, on which a wide triangular ploughshare with a wing was put on. A fixed metal blade was attached to the plowshare. The plows could vary in the shape of the plowshare, the location of the plow, could have the rudiment of a runner characteristic of the plow, but the attachment of the pulling force was always high.

Improved versions of one-sided cox bore different names: kurashimka, chegandinka and others. They became widespread in Siberia and the Urals. The improved one-sided plows had a significant advantage over the two-sided plows. They plowed deeper, took the seam wider, loosened the soil better, were more productive in their work. However, they were expensive, they wore out rather quickly, and in the event of a breakdown it was difficult to repair them in the field. In addition, they demanded very strong horses for the team.

The plow is multi-toothed or a pump, or a shaker

Tillage implement with high pulling force attachment, type of plow. A characteristic feature of the multi-toothed plow was the presence of three to six broad-pointed, blunt plows on the rass, as well as the absence of a police officer. Such a plow was used for embedding in spring after autumn plowing of spring crops, covering oat seeds with earth, plowing the land after plowing with a two-sided plow or one-sided plow. The multi-tine plow was ineffective at work.

The representative of the Novgorod zemstvo, priest Serpukhov, characterized the multi-toothed plow: “With pumps with blunt broad-pointed pumps, like cow tongues, none of the main goals or conditions is achieved during the cultivation of the land, the pump is almost carried on the hands of the worker, otherwise the earth and oats are drilled, and when raised This land is left in heaps and oats in ridges, and does not go deeper into the ground. It is difficult to understand that for the purpose of introducing this into agriculture, the peasants cultivate the land in a row after sowing, or, as they usually say, fill up the oats with a tiller. But observation of these actions does not in the least speak in their favor, but rather discourages them otherwise ”(Serpukhov 1866, V, 3). Multi-toothed plows in the 19th century met quite rarely, although at an earlier time, in the XII-XIV centuries, they were widespread until they were supplanted by more advanced types of soks.

Plow plow or skewer, dace, spruce, nyk

A tool for plowing, harrowing and embedding seeds with earth, used on the undercut - a forest clearing in which the forest was cut down and burned, preparing the land for arable land. It was made from several (from 3 to 8) armor plates - plates with branches on one side, obtained from the trunks of spruces or pines, split longitudinally. Bronnitsy were fastened with two crossbars located on two opposite sides of the knot.

The material for their fastening was thin trunks of young oak trees, bird cherry branches, bast or vine. Sometimes the armor was tied to each other without crossbars. To the two extreme armors, longer than the central ones, they tied the strings, with the help of which the horse was harnessed. Sometimes the extreme armor plates were so long that they were used as shafts. The teeth of the knot were twigs, pointed at the ends, up to 80 cm long. On the undercut, the knot was used to loosen a layer of earth mixed with ash.

Teeth-boughs, strong and at the same time flexible, well traced the undercut, and bumping into the roots, inevitable in such a field, springy jumped over them, without breaking at all. Sukovatka was distributed in the northern and northwestern provinces of European Russia, mainly in forest areas. Sukovatki, distinguished by the simplicity of their structure, were known to the Eastern Slavs even in the era of Ancient Rus. Some researchers believe that it was the knotweed that was the cultivating tool on the basis of which the plow was created. The development of the plow from the knot took place by reducing the number of teeth in each of the armor plates, and then reducing the number and size of the plates themselves.

Saban

A soil tillage implement with a low pulling force attachment, a type of plow, was used to lift the deposit. This weapon was known to the Russians in two versions: one-blade and two-blade saban. The one-blade saban in many respects repeated the Little Russian plow and consisted of a runner (sole), a ploughshare, a blade, a cutter, a stand, a uterus, handles, a front end and a bead.

It differed from the Little Russian plow by a ploughshare, which had the shape of a versatile triangle, a more curved cutter that touched the ground with the lower end of the butt and was at a considerable distance from the ploughshare, as well as a greater curvature of the bead. In addition, the wooden stand that fastened the runner to the beam was replaced here with an iron one, and the ploughshare was also connected to the beam with an iron rod. The Saban had one or two iron mouldboards, which resembled wings attached near a plowshare. The Saban, like the Little Russian plow, was a heavy, bulky tool. He was dragged with difficulty by two horses.

Usually three to five horses or three to six pairs of oxen were harnessed to it. The two-blade saban had a runner made of two thick wooden beams, at the ends of which there were plowshares in the shape of a right-angled triangle, located horizontally towards the ground. The runner was connected to the handles. With their help, the plowman controlled the Saban. One end of a strongly curved bead was attached to the runner close to the share, the other end was inserted into the front end with wheels. A cutter in the form of a knife directed with the blade forward was inserted into the bead in front of the plowshares. The dump was two wooden planks attached to the handles and the bead to the right and left of the sole.

The two-dog saban was a lighter tool than the one-dog one. Usually two horses were harnessed to it. The Saban glided well on the ground on the runner, the cutter cut off the soil layer vertically, and the plowshares cut it horizontally. The plowing depth was adjusted using wedges inserted from above or below the rear end of the bead. If the wedges were inserted from above, then the plowing was shallower, if from below, it was deeper. Sabans were distributed mainly in the provinces of the Lower Volga region and in the Urals.